Soy Basics & Biochemistry

A comprehensive scientific exploration of Glycine max, from molecular structures to physiological impacts and nutritional density.

1. The Botanical Foundation of Soy

The soybean (Glycine max) is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses. Its domestication dates back thousands of years to ancient China, where it was revered as one of the five sacred grains. Unlike most plant foods, soy is biologically distinct due to its high protein concentration and unique phytochemical profile. As a nitrogen-fixing plant, soy plays a critical role in sustainable agriculture, forming a symbiotic relationship with Rhizobium bacteria to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants.

From a botanical perspective, the soybean consists of the hull, the hypocotyl, and two cotyledons. The cotyledons store the bulk of the nutrients, particularly the proteins and lipids that define the crop’s economic and nutritional value. Understanding what is soy nutrition facts requires a deep dive into these storage organs, which contain a complex matrix of enzymes, structural proteins, and bioactive molecules designed to support the germinating seed.

2. Macronutrient Profiling: What is Soy Nutrition Facts?

Soy is often referred to as the ‘meat of the field’ due to its exceptional protein quality. It is one of the few plant-based sources that provides all nine essential amino acids in proportions required for human physiological function. This makes the PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score) of soy comparable to animal proteins like egg whites or casein.

Proteins

Comprising 36-40% of the dry weight, primarily glycinin and beta-conglycinin, which exhibit lipid-lowering properties.

Lipids

Approximately 20% oil content, rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids including alpha-linolenic acid (Omega-3) and linoleic acid.

Carbohydrates

Contains soluble sugars like sucrose and insoluble fibers, as well as oligosaccharides such as raffinose and stachyose.

When analyzing what is soy nutrition facts, one must account for the density of micronutrients. Soybeans are an excellent source of B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, niacin), folate, and vitamin K. Furthermore, the mineral profile includes substantial amounts of potassium, magnesium, and iron. However, the biochemistry of these minerals is influenced by the presence of phytates, which we will explore in subsequent sections.

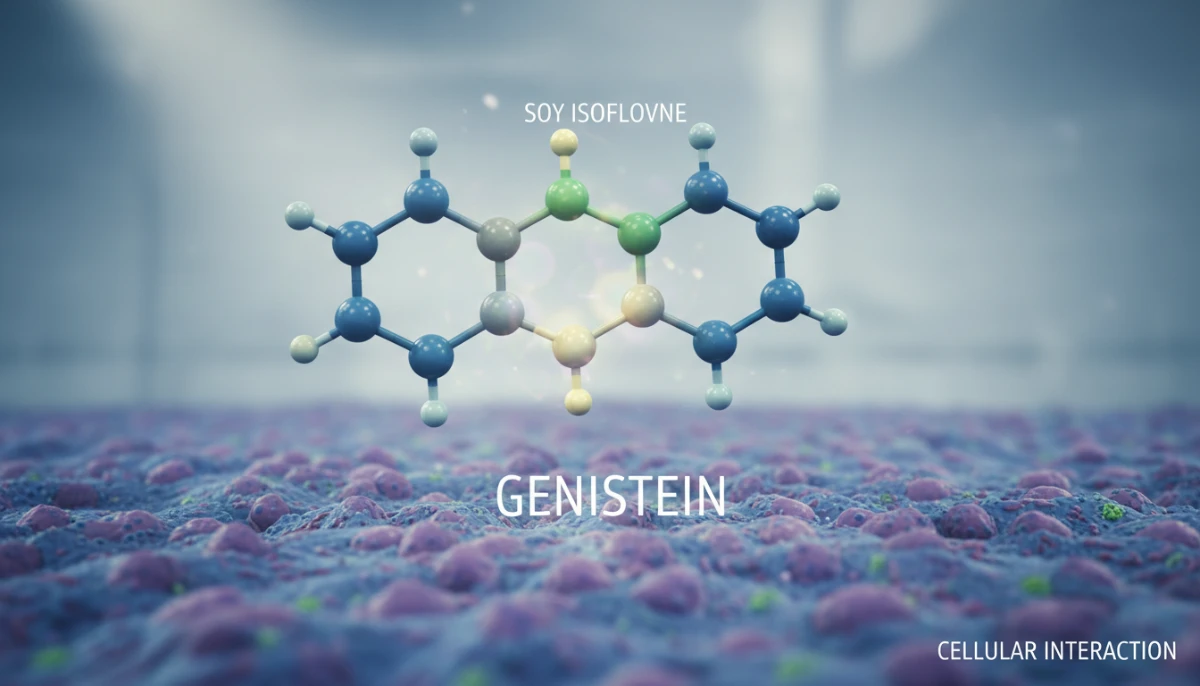

3. The Biochemistry of Isoflavones

The most scientifically intriguing component of soy is its concentration of isoflavones, a subclass of flavonoids known for their phytoestrogenic properties. The primary isoflavones in soy are genistein, daidzein, and glycitein. These compounds are structurally similar to 17-beta-estradiol, the primary female sex hormone, allowing them to bind to estrogen receptors (ER-alpha and ER-beta) throughout the human body.

“Soy isoflavones act as Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs). Depending on the tissue type and the endogenous estrogen levels, they can exert either weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects.”

Beyond their hormonal mimicry, isoflavones are potent antioxidants. They modulate cell signaling pathways, including the inhibition of protein tyrosine kinases, which plays a role in suppressing oncogenic transformation. The metabolic fate of these isoflavones is highly dependent on the individual’s gut microbiome. For instance, daidzein can be converted into equol, a metabolite with significantly higher biological activity, only by individuals possessing specific intestinal bacterial strains.

4. Antinutrients and Bioavailability

Like many seeds, soybeans contain antinutritional factors—biochemical compounds that evolved to protect the plant from predation but can interfere with human digestion. These include trypsin inhibitors, lectins, and phytic acid. Trypsin inhibitors interfere with the enzyme trypsin, which is essential for protein digestion in the small intestine. Fortunately, these are heat-labile, meaning cooking or thermal processing deactivates them.

Phytic acid (inositol hexaphosphate) is another significant component. It binds to minerals like calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc, forming insoluble salts that the human body cannot readily absorb. Fermentation, as seen in traditional foods like tempeh and miso, significantly reduces phytic acid levels by activating the enzyme phytase, thereby increasing the bioavailability of the soy’s mineral content. This process highlights why the form of soy consumed is just as important as the raw nutrition facts.

5. Physiological Mechanisms and Human Health

The consumption of soy has been linked to numerous health outcomes through various biochemical pathways. In cardiovascular health, soy protein has been shown to lower LDL cholesterol by up to 3-5%, likely through the upregulation of LDL receptors in the liver. This effect is attributed to the synergistic action of the amino acid profile and the associated isoflavones.

In bone health, isoflavones may help maintain bone mineral density in postmenopausal women by stimulating osteoblast activity. Furthermore, there is ongoing research into the protective effects of soy against certain hormone-dependent cancers. Epidemiological studies suggest that early-life soy consumption may reduce the lifetime risk of breast cancer by inducing more differentiated cellular structures in mammary tissue.

6. Industrial Processing and Chemical Integrity

The modern food industry utilizes soy in various forms, from whole edamame to soy protein isolates (SPI). The extraction of SPI involves alkaline solubilization and acid precipitation, which concentrates protein but can strip away the beneficial fiber and some of the isoflavones. Furthermore, hexane is often used as a solvent in the oil extraction process, raising questions about residual chemical levels, though industry standards maintain these are within safe limits.

It is essential for consumers to distinguish between whole-food soy and ultra-processed soy additives found in many snacks and meat alternatives. The biochemical synergy found in the whole bean—the interaction between its fiber, fats, proteins, and phytochemicals—is often compromised during heavy industrial refinement. For optimal health benefits, the focus should remain on minimally processed versions such as tofu, tempeh, and whole soybeans.

7. Frequently Asked Questions

Does soy impact testosterone levels in men?

Extensive clinical meta-analyses have concluded that neither soy foods nor isoflavone supplements affect bioavailable testosterone levels or estrogen levels in men. The phytoestrogens in soy are fundamentally different from mammalian estrogen.

Is soy milk as nutritious as cow milk?

Soy milk is the most nutritionally comparable plant milk to cow milk. It contains similar protein levels (8g per cup) and is typically fortified with calcium and vitamin D to match or exceed the profile of dairy.

How much soy is safe to eat daily?

Research suggests that 2-4 servings per day of whole soy foods are perfectly safe and potentially beneficial for most adults as part of a balanced diet.