Soy Consumption and Precocious Puberty: Separating Myth from Medical Science

An exhaustive review of phytoestrogens, pediatric endocrine development, and the current scientific consensus on soy nutrition.

The Great Nutritional Controversy

In recent decades, few foods have sparked as much intense debate as soy. As a cornerstone of plant-based diets and a common ingredient in infant formulas, its prevalence in the Western diet is undeniable. However, with its rise in popularity has come a wave of concern regarding its hormonal effects, specifically the potential for soy consumption to trigger precocious puberty in children. Precocious puberty—the onset of sexual development before the age of eight in girls and nine in boys—carries significant physical, psychological, and social implications. Parents and health professionals alike are asking: Does the genistein in soy mimic human estrogen enough to disrupt the delicate biological clock of childhood development?

This comprehensive architectural analysis dives deep into the endocrine system, the molecular structure of phytoestrogens, and the vast body of peer-reviewed research to determine if soy is a genuine risk factor or a misunderstood nutrient. To understand the relationship between soy and puberty, we must first look at the mechanisms of human growth and how external substances interact with our internal hormonal receptors.

Defining Precocious Puberty: The Biological Context

Puberty is a complex physiological process orchestrated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Under normal circumstances, the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones, in turn, stimulate the gonads (ovaries or testes) to produce sex steroids—estrogen and testosterone—which drive physical maturation. Precocious puberty is categorized into two main types: Central Precocious Puberty (GnRH-dependent) and Peripheral Precocious Puberty (GnRH-independent).

Central precocious puberty involves the premature activation of the entire HPG axis, mirroring the normal sequence of puberty but at an abnormally early age. Peripheral precocious puberty, however, occurs when the sex hormones themselves are present in the body without the signal from the brain, often due to issues with the adrenal glands, ovaries, or exposure to external (exogenous) estrogens. The concern regarding soy is primarily focused on the possibility that its isoflavones could act as exogenous estrogens, bypassing the brain’s control and stimulating breast tissue or other secondary sexual characteristics prematurely.

Understanding Soy Isoflavones: Phytoestrogen Mechanics

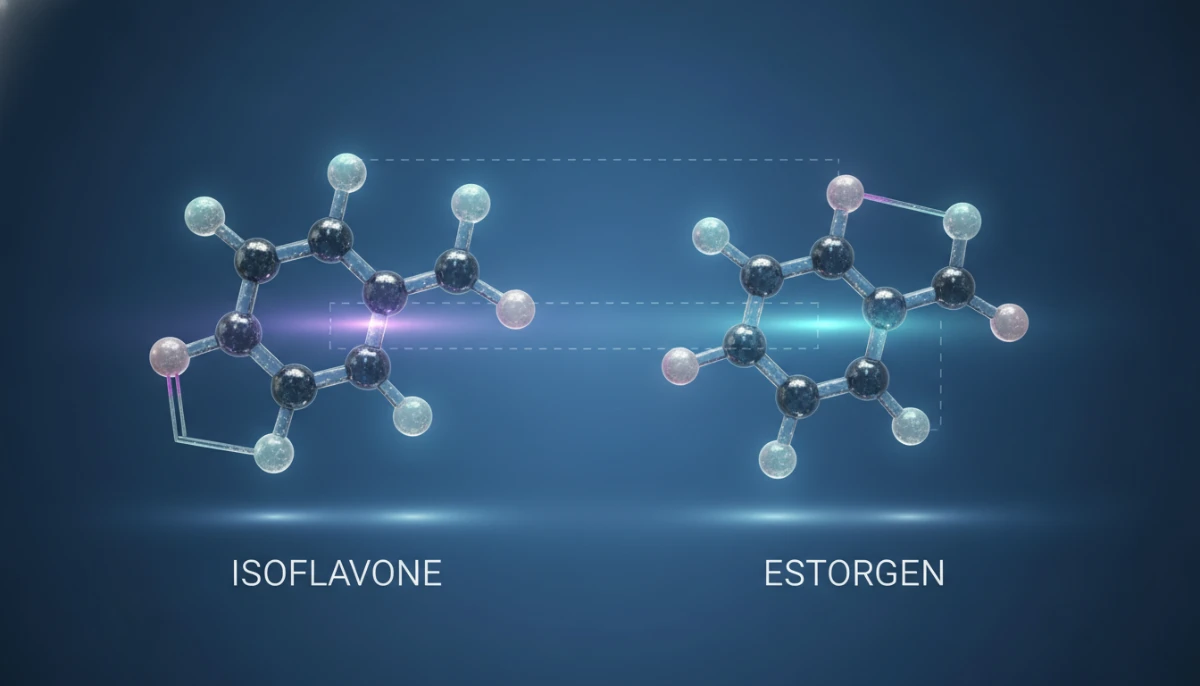

The primary compounds of interest in soy are isoflavones, specifically genistein, daidzein, and glycitein. These are classified as phytoestrogens—plant-derived compounds that are structurally similar to 17β-estradiol, the primary female sex hormone. This structural similarity allows isoflavones to bind to estrogen receptors (ERs) in the human body. However, the term “estrogen-like” can be misleading without clinical context. In humans, there are two main types of estrogen receptors: ER-alpha and ER-beta.

ER-Alpha Receptors

Located primarily in the uterus and breast tissue. High-affinity binding here is typically associated with traditional estrogenic effects and growth stimulation.

ER-Beta Receptors

Found in the brain, bone, and vascular system. Phytoestrogens have a much higher affinity for ER-beta, where they often act as Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs).

Crucially, soy isoflavones are significantly weaker than human estrogen—estimates suggest they are 1,000 to 10,000 times less potent. Because they bind preferentially to ER-beta and only weakly to ER-alpha, they can sometimes act as estrogen antagonists, effectively blocking more potent endogenous estrogens from binding to receptors. This nuance is why soy is often studied for its potentially protective effects against certain hormone-dependent cancers rather than as a stimulator of early development.

Clinical Evidence: What the Human Studies Reveal

Much of the initial alarm regarding soy and puberty originated from animal studies, particularly in rodents. Rats and mice metabolize isoflavones differently than humans, and many studies involved injecting high doses of genistein directly into the animal. When we look at human epidemiological data, the picture changes significantly. Large-scale longitudinal studies have consistently failed to find a definitive link between moderate soy consumption and the onset of precocious puberty.

For instance, the Adventist Health Study-2, which followed thousands of children, observed that girls with high soy intake did not experience menarche (the start of menstruation) significantly earlier than those with low soy intake. In fact, some research suggests that high soy intake in childhood might even lead to a slightly *later* onset of puberty, which is associated with a lower lifetime risk of breast cancer. Furthermore, clinical reviews of infants fed soy-based formula—where soy intake is at its highest relative to body weight—have shown no clinically significant differences in timing of puberty or reproductive health in adulthood compared to those fed cow’s milk formula.

Alternative Drivers: The Real Culprits Behind Early Puberty

If soy isn’t the primary driver, why are we seeing a global trend toward earlier puberty? Researchers point to several more significant environmental and lifestyle factors. Chief among these is childhood obesity. Adipose (fat) tissue is metabolically active; it produces and stores hormones and contains the enzyme aromatase, which converts an drogens into estrogens. Higher levels of body fat are strongly correlated with earlier breast development in girls.

Additionally, exposure to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) found in plastics (BPA, phthalates), pesticides, and certain personal care products (parabens) has been linked to hormonal disruption. Unlike phytoestrogens, these chemicals often lack the beneficial “antagonist” properties of soy and can interfere more aggressively with the HPG axis. Stress, household environment, and nutritional shifts toward ultra-processed foods are also significant variables that dwarf the impact of a bowl of edamame or a glass of soy milk.

The Health Benefits of Soy for Children

Rather than being a food to fear, soy can be a nutrient-dense addition to a child’s diet. It is one of the few plant-based sources of complete protein, containing all nine essential amino acids. It is also rich in calcium (when fortified), iron, and fiber. For children with cow’s milk protein allergies or those in vegan/vegetarian households, soy serves as a vital bridge for growth and development.

- Heart Health: Early exposure to soy protein may help establish healthy cholesterol levels.

- Bone Density: Isoflavones play a role in bone metabolism, potentially strengthening the skeletal frame during growth spurts.

- Cancer Prevention: Some evidence suggests that soy consumption during childhood and adolescence provides a protective effect against breast and prostate cancers later in life.

Practical Advice for Parents: Balance and Moderation

The consensus among major health organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), is that soy is safe for children. However, as with any food, moderation and variety are key. Parents should focus on whole or minimally processed soy foods like tofu, tempeh, and edamame rather than highly processed soy protein isolates found in some snacks and bars. The advancements in food technology, such as Precision Fermentation: Soy’s Role in Next-Gen Proteins, are continually shaping our understanding of soy-derived products. Integrating soy as one of many protein sources—alongside beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, and, if desired, lean meats and dairy—ensures a broad spectrum of nutrients, suitable for everyday meals and even Classic Kiwi Potlucks. For more detailed preparation tips, explore our guide on Mastering Soy Cooking & Prep, and for specific appliance-based recipes, consult the Ultimate Air Fryer Tofu Guide.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can soy cause ‘man boobs’ (gynecomastia) in boys?

For a comprehensive understanding of male hormonal health, refer to our article on Men’s Health: Testosterone. Clinical reviews have shown that isoflavones do not affect testosterone levels or estrogen levels in males at normal dietary amounts. The cases often cited involve extreme consumption levels that do not reflect a standard diet.

Should I avoid soy formula?

While breast milk is best, soy formula is a safe alternative for infants with galactosemia or hereditary lactase deficiency. Studies of adults who were fed soy formula as infants show no adverse reproductive or hormonal effects.

How much soy is too much?

For children, 1-2 servings of soy per day is considered perfectly safe and beneficial. A serving might be a cup of soy milk or a half-cup of tofu.