Modern Soy Safety & Biochemistry: A Comprehensive Scientific Review

For decades, the humble soybean has remained at the center of a swirling vortex of nutritional controversy. Is it a superfood capable of reducing chronic disease risk, or a hormonal disruptor that should be avoided at all costs? In this exhaustive 2,200-word analysis, we bridge the gap between anecdotal health myths and rigorous clinical biochemistry to determine once and for all: is soy safe to eat?

1. The Biochemical Profile of Glycine Max

The soybean (Glycine max) is a legume species native to East Asia, widely recognized for its unique nutritional density. Unlike most plant proteins, soy is considered a “complete protein,” containing all nine essential amino acids—histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine—in ratios that support human growth and maintenance. Beyond its protein content, soy is a significant source of dietary fiber, polyunsaturated fats, and a complex array of micronutrients, including molybdenum, copper, manganese, and phosphorus.

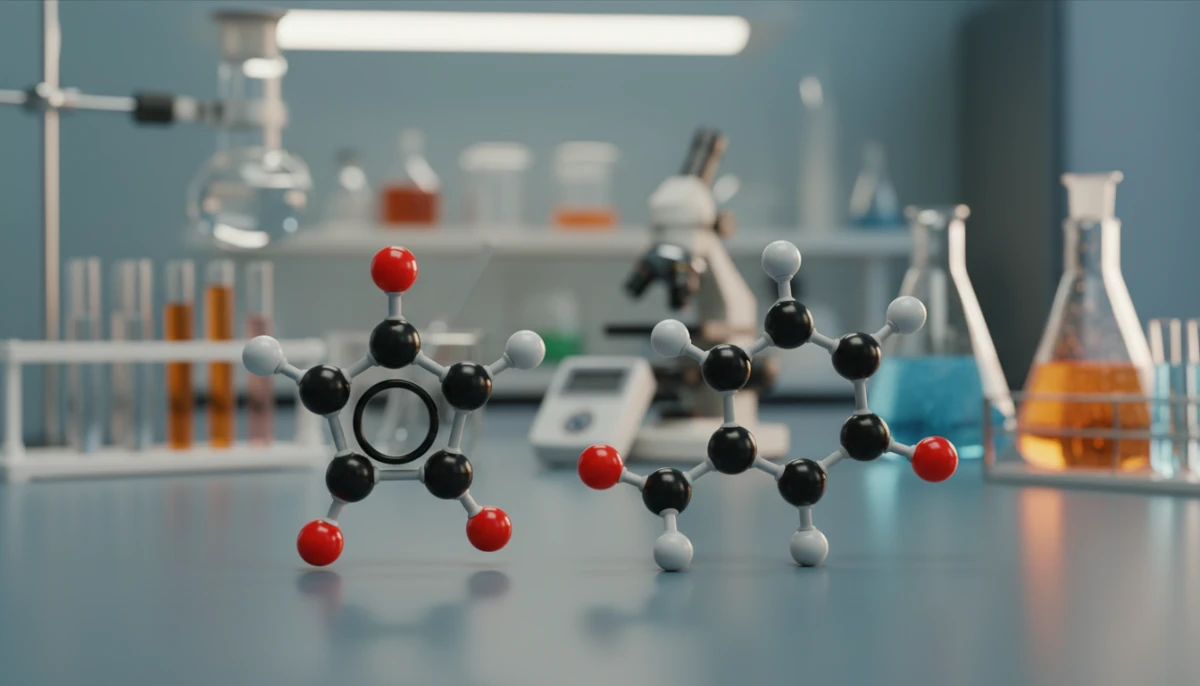

However, the primary interest in soy safety stems from its high concentration of isoflavones. These polyphenolic compounds, primarily genistein, daidzein, and glycitein, belong to a class of molecules known as phytoestrogens. At the molecular level, isoflavones possess a chemical structure strikingly similar to 17β-estradiol, the primary female sex hormone. This structural homology allows isoflavones to bind to estrogen receptors (ERs) throughout the human body, though with significantly lower affinity than endogenous estrogen.

To understand the metabolic fate of soy, one must examine the role of the gut microbiome. When soy is consumed, isoflavone glucosides are hydrolyzed by intestinal bacteria into their aglycone forms. For approximately 30-50% of the population, specific bacteria can further metabolize daidzein into equol, a compound with even higher estrogenic activity. This inter-individual variability in gut microflora explains why some individuals may derive more significant health benefits—or experience different physiological responses—from soy consumption than others. The question of whether soy is safe to eat must therefore be viewed through the lens of individual metabolic capacity.

2. Decoding the Phytoestrogen Paradox

The most frequent concern regarding soy is its potential to disrupt hormonal balance. The term “phytoestrogen” is often misunderstood as synonymous with “estrogen.” In reality, soy isoflavones act as Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs). The human body contains two primary types of estrogen receptors: Alpha (ERα) and Beta (ERβ). ERα receptors are prevalent in breast and uterine tissue, where their activation can stimulate cell proliferation. ERβ receptors, conversely, are found in bone, the cardiovascular system, and the brain, where they generally promote protective effects.

Crucially, soy isoflavones have a significantly higher affinity for ERβ than for ERα. This means that soy often exerts anti-estrogenic effects in tissues with high ERα concentrations (by blocking more potent endogenous estrogens) while exerting pro-estrogenic effects in tissues with high ERβ concentrations. This dual-action mechanism explains why soy can simultaneously help mitigate menopausal symptoms like hot flashes while potentially offering protective benefits against certain hormone-dependent cancers. For the average healthy adult, the biochemical evidence suggests that the consumption of moderate amounts of soy does not lead to feminization or pathological hormonal shifts.

The dosages used in animal studies that suggested harm are often orders of magnitude higher than what humans consume in a standard diet. Rodents also metabolize isoflavones very differently than humans, producing much higher levels of circulating active compounds. Longitudinal human studies consistently show that moderate intake—defined as 1-3 servings of whole soy foods per day—is not associated with adverse hormonal changes in either men or women. This distinction between rodent-based pharmacology and human epidemiology is vital for a nuanced understanding of soy safety.

3. Cardiovascular Implications & Lipid Profiles

One of the strongest arguments for soy safety and inclusion in the diet is its impact on cardiovascular health. In 1999, the FDA authorized a health claim stating that 25 grams of soy protein a day, as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, may reduce the risk of heart disease. While the FDA has recently considered re-evaluating the “unqualified” status of this claim to a “qualified” one due to inconsistent results in some modern trials, the consensus remains overwhelmingly positive.

Soy protein consumption has been shown to reduce LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol—often referred to as “bad” cholesterol—by approximately 3% to 5%. While this reduction appears modest, at a population level, it translates to a significant decrease in cardiovascular events. The mechanism is multifaceted: soy protein may upregulate LDL receptors in the liver, facilitating the clearance of cholesterol from the bloodstream. Furthermore, the high fiber content in whole soy foods like edamame and tempeh further aids in lipid management by binding bile acids in the digestive tract.

Beyond cholesterol, soy contains bioactive peptides that may exert antihypertensive effects by inhibiting the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE). Maintaining healthy blood pressure is a critical factor in preventing stroke and myocardial infarction. Therefore, from a cardiovascular standpoint, the question isn’t just “is soy safe to eat?” but rather “is soy a strategic dietary tool for longevity?” The inclusion of soy as a replacement for processed meats or high-fat dairy provides a dual benefit: the removal of pro-inflammatory saturated fats and the addition of heart-protective phytonutrients.

4. Soy in Oncology: Protective or Provocative?

The relationship between soy and cancer—specifically breast cancer—is perhaps the most debated topic in soy biochemistry. The initial fear was that because estrogen can drive the growth of many breast cancers, phytoestrogens might do the same. However, large-scale epidemiological studies, such as the Shanghai Women’s Health Study, have shown the opposite. Women who consume high amounts of soy from childhood through adulthood have a significantly lower risk of developing breast cancer compared to those with low intake.

For breast cancer survivors, the American Cancer Society and the American Institute for Cancer Research have concluded that soy consumption is safe. Multiple meta-analyses of survivor cohorts indicate that soy intake is either neutral or associated with a reduced risk of cancer recurrence and mortality. This is likely due to the SERM behavior mentioned earlier; isoflavones may competitively inhibit the more potent endogenous estrogens from binding to breast tissue receptors.

In men, soy consumption has been linked to a reduced risk of prostate cancer. A meta-analysis published in ‘Nutrients’ found that total soy food intake was significantly associated with a 29% reduction in prostate cancer risk. The hypothesized mechanism involves genistein’s ability to inhibit the enzymes responsible for prostate cell proliferation and its role in promoting apoptosis (programmed cell death) in malignant cells. These findings suggest that soy may play a preventative role in oncology rather than a causative one.

5. Testosterone and Men’s Reproductive Health

A persistent cultural myth suggests that soy consumption leads to decreased testosterone, increased estrogen, and “feminization” in men. This concern is largely based on two isolated case reports of individuals consuming extreme quantities of soy (e.g., three liters of soy milk daily) while having otherwise poor nutrition. When we look at the clinical data, the narrative changes entirely.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of over 40 clinical trials concluded that neither soy protein nor isoflavone supplements have any effect on total testosterone, free testosterone, or estrogen levels in men. Furthermore, soy does not appear to negatively impact sperm concentration, motility, or morphology. For athletes and bodybuilders, soy protein has been shown to be just as effective as whey protein in promoting muscle protein synthesis and strength gains when paired with resistance training. The biochemical reality is that soy is a high-quality, safe protein source for men that does not compromise masculinity or hormonal health.

6. Thyroid Function and Goitrogenesis

Soy contains compounds called goitrogens, which can theoretically interfere with the thyroid’s ability to uptake iodine. This has led to concerns that soy might cause or worsen hypothyroidism. However, clinical studies on healthy individuals with adequate iodine intake have shown that soy consumption does not affect thyroid hormone levels. The “is soy safe to eat” question for thyroid health depends primarily on iodine status.

For individuals with existing hypothyroidism who are taking synthetic thyroid hormone (Levothyroxine), soy can interfere with the absorption of the medication. This does not mean these individuals must avoid soy; rather, they should be consistent in their soy intake and ensure they take their medication on an empty stomach, typically 4 hours apart from soy consumption. As long as iodine levels are sufficient, soy does not pose a threat to thyroid health in the general population.

7. Processing Dynamics: Whole vs. Ultra-Processed

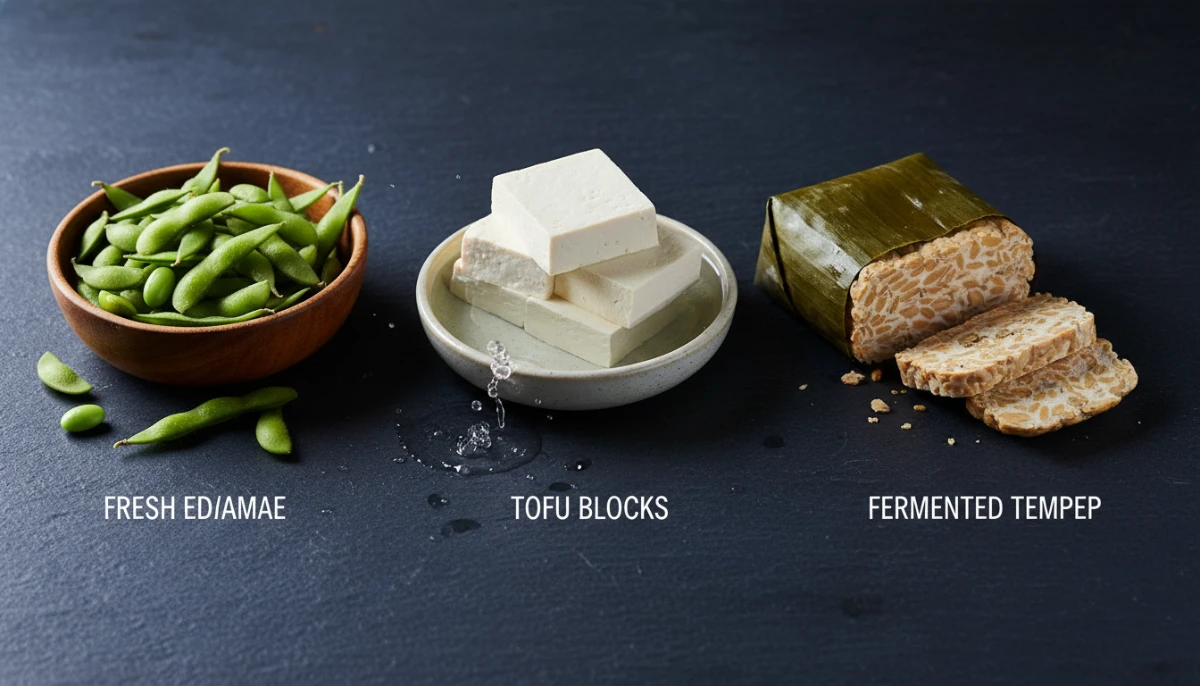

Not all soy is created equal. The safety and nutritional value of soy depend heavily on how it is processed. Whole, traditionally fermented soy foods like tempeh, miso, and natto are often considered the gold standard. Fermentation reduces “anti-nutrients” like phytic acid (which can inhibit mineral absorption) and increases the bioavailability of isoflavones. Tofu and edamame are also excellent, minimally processed options.

On the other end of the spectrum are ultra-processed soy derivatives, such as soy protein isolates (SPI), textured vegetable protein (TVP), and soy-based meat analogues. While these products are convenient and safe in moderation, they lack the fiber and complex nutrient profile of the whole bean. Furthermore, some industrial processing methods use hexane as a solvent to extract oil from the beans. While the amounts of residual hexane in finished products are negligible and considered safe by regulatory bodies, health-conscious consumers often prefer organic or “expeller-pressed” soy products to avoid chemical solvents.

Genetically Modified (GMO) soy is another point of contention. Over 90% of the soy grown in the United States is genetically modified to be herbicide-resistant. While major health organizations like the WHO and EFSA maintain that GMO soy is safe for consumption, many choose non-GMO or organic soy to reduce exposure to glyphosate residues and to support more sustainable agricultural practices. Choosing organic soy ensures that the crop is non-GMO and grown without synthetic pesticides.

8. Summary Guidelines & Conclusion

Is soy safe to eat? Based on the totality of current scientific evidence, the answer is a resounding yes for the vast majority of the population. Soy is a nutrient-dense, high-quality protein source that offers significant benefits for cardiovascular health, bone density, and potentially cancer prevention. To maximize the benefits and minimize risks, consumers should focus on minimally processed, whole soy foods such as tofu, tempeh, edamame, and soy milk. Aiming for 1-2 servings daily is a safe and evidence-based recommendation for most adults.

The biochemical complexity of soy—its SERM activity, its complete amino acid profile, and its impact on lipid metabolism—renders it one of the most sophisticated tools in a plant-forward diet. While individual health conditions like iodine deficiency or specific medication interactions require attention, the generalized fear of soy is largely unsupported by modern clinical data. As we move toward a more sustainable global food system, soy will undoubtedly play a central role as a safe, efficient, and health-promoting protein source.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Does soy cause ‘man boobs’ (gynecomastia)?

No. Clinical studies have shown that even high levels of soy intake do not increase estrogen levels or cause feminizing effects in men. The few case studies suggesting this involved extreme, abnormal consumption (3+ quarts of soy milk daily) alongside other nutritional deficiencies.

Is soy safe for children and infants?

Soy-based infant formulas have been used for decades with no documented adverse effects on development or reproductive health. However, for older children, whole soy foods are preferred over processed snacks. Always consult a pediatrician for infant nutrition.

Can I eat soy if I have a history of breast cancer?

Current research suggests that moderate soy intake (1-2 servings/day) is safe and may even be protective for breast cancer survivors. It does not interfere with common treatments like Tamoxifen and may reduce the risk of recurrence.

Should I only eat fermented soy?

While fermented soy (tempeh, miso) offers additional probiotic benefits and better mineral absorption, unfermented soy (tofu, edamame) is also highly nutritious and safe. A mix of both is ideal.