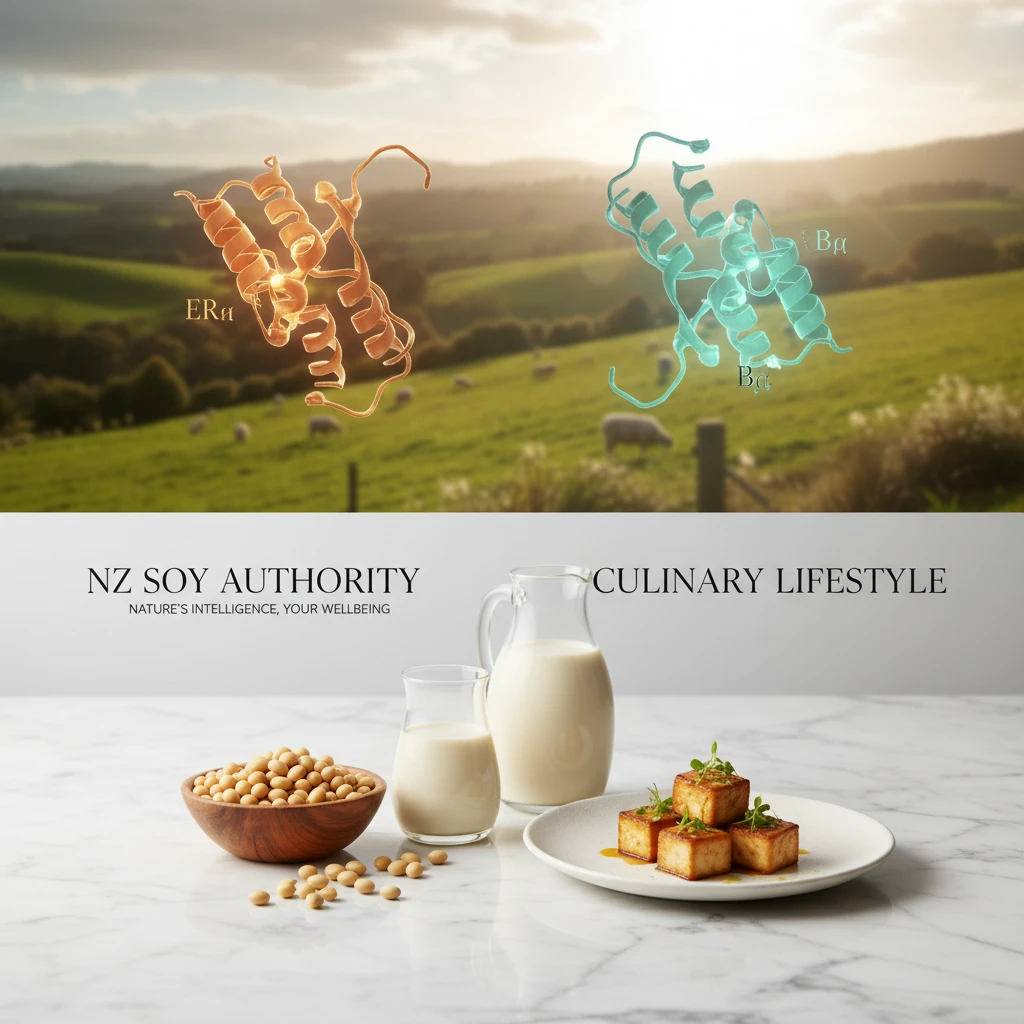

Estrogen Receptors (Alpha vs Beta): The Biological Mechanics of Hormonal Health

Estrogen Receptors (ERs) are a group of intracellular proteins that function as ligand-activated transcription factors, primarily stimulated by the hormone estrogen. There are two distinct subtypes found in the human body: Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα), which typically drives cell proliferation in reproductive tissues, and Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ), which often acts as a modulator or inhibitor of ERα, playing a crucial protective role in bone maintenance, cardiovascular health, and neurological function.

Editor’s Note from the NZ Soy Authority: Understanding the distinction between these two receptors is critical for interpreting the health effects of soy. Phytoestrogens found in soy products do not behave identically to human estrogen; their health benefits are largely attributed to their selective preference for binding with the Beta receptor over the Alpha receptor.

The Architecture of Nuclear Receptors

To understand the nuanced dance between estrogen and the body, one must first understand the stage upon which they operate: the nuclear receptor superfamily. Estrogen receptors are not merely passive docking bays; they are dynamic transcription factors that regulate gene expression. When a ligand (such as the endogenous hormone 17β-estradiol or a dietary phytoestrogen) binds to an ER, the receptor undergoes a conformational change. This change allows the receptor to dimerize—pair up—and bind to specific DNA sequences known as Estrogen Response Elements (EREs).

For decades, scientists believed there was only one estrogen receptor. It wasn’t until 1996 that Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ) was discovered, fundamentally changing our understanding of endocrinology. We now know that the biological response to estrogen is determined by the balance and ratio of these two receptors—Alpha and Beta—within a specific tissue.

While they share significant structural homology, particularly in their DNA-binding domains (over 95% identical), their Ligand Binding Domains (LBD) differ significantly. This structural variance is the key to why synthetic drugs and natural compounds like soy isoflavones can have vastly different effects on the body compared to the body’s own estrogen.

Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα): The Proliferator

Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα), encoded by the ESR1 gene, is the “classic” receptor. Historically, when medical literature referred to estrogenic activity, they were largely describing the activation of ERα. This receptor is the primary driver of the feminizing effects of estrogen and is essential for reproductive function.

Mechanism of Action

When activated, ERα generally promotes cell proliferation and growth. In the context of puberty and the menstrual cycle, this is a necessary function. It stimulates the thickening of the uterine lining and the development of breast tissue. However, because its primary mode is “growth,” overstimulation of ERα is strongly associated with an increased risk of hormone-sensitive cancers, such as breast and endometrial cancer.

Key Functions of ERα

- Reproductive Health: Essential for ovulation and the maintenance of pregnancy.

- Metabolic Regulation: Plays a role in glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity.

- Skeletal Physiology: Contributes to the closure of epiphyseal plates (growth plates) in bones during puberty.

The dominance of ERα in specific tissues explains why unopposed estrogen therapy (estrogen without progesterone) fell out of favor for women with a uterus; the unchecked stimulation of ERα led to hyperplasia. Understanding this risk profile is essential when comparing endogenous hormones to dietary modulators.

Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ): The Regulator

Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ), encoded by the ESR2 gene, acts as the sophisticated counterbalance to Alpha. If ERα is the accelerator, ERβ often functions as the brake. Research indicates that when both receptors are present in a cell, ERβ can inhibit the transcriptional activity of ERα, thereby dampening the proliferative signal.

The Protective Phenotype

ERβ is widely regarded as having an anti-proliferative and anti-carcinogenic role. Its activation sends signals to cells to differentiate (mature) rather than simply divide. This distinction is vital for the NZ Soy Authority audience, as the health benefits associated with soy consumption are largely mediated through this specific receptor pathway.

Key Functions of ERβ

- Neurological Protection: ERβ is abundant in the hippocampus and cortex, playing a role in memory, cognition, and potentially protecting against neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

- Cardiovascular Health: It helps maintain the flexibility of blood vessels and regulates blood pressure.

- Bone Density: While Alpha plays a role, Beta is crucial for the maintenance of cancellous bone, reducing osteoporosis risk.

- Prostate Health: In men, ERβ expression is high in the prostate and is thought to protect against hyperplasia and cancer.

Tissue Distribution: Location Matters

The physiological outcome of estrogen exposure depends entirely on where these receptors are located. The body does not have a uniform distribution of ERα and ERβ. This heterogeneity allows for tissue-specific responses.

ERα Dominant Tissues:

- Uterus (Endometrium)

- Breast (Mammary Glands)

- Hypothalamus

- Pituitary Gland

ERβ Dominant Tissues:

- Ovaries (Granulosa cells)

- Colon

- Lung

- Prostate

- Bone Marrow

- Endothelium (lining of blood vessels)

This distribution explains why compounds that selectively target ERβ can support bone and heart health without stimulating uterine or breast tissue growth. This concept is known as Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulation (SERM).

The Soy Connection: Phytoestrogens as SERMs

This is the intersection where biochemistry meets culinary lifestyle. For our New Zealand audience incorporating soy into their diets—whether through tofu, tempeh, or soy milk—understanding receptor affinity is the key to debunking myths.

Soy contains isoflavones, primarily Genistein and Daidzein. These are phytoestrogens (plant estrogens). Critics often claim that because they look like estrogen, they must cause the same problems as excess human estrogen (like cancer risk). However, this ignores the affinity differential.

The Affinity Differential

Genistein, the most abundant isoflavone in soy, has a significantly higher binding affinity for ERβ than for ERα. Studies suggest Genistein binds to ERβ with 20 to 30 times the affinity it has for ERα.

When you consume soy, the isoflavones preferentially flood the Beta receptors. This triggers the beneficial, protective, and anti-proliferative pathways associated with ERβ, while leaving the Alpha receptors largely unstimulated. In fact, by occupying the receptor sites and recruiting co-repressors, phytoestrogens can sometimes block stronger endogenous estrogens from binding, potentially lowering the risk of estrogen-dependent cancers.

For more deep data on biochemical interactions, you can refer to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) regarding nuclear receptor signaling.

Clinical Implications for Health and Disease

The Alpha vs. Beta dichotomy is currently driving pharmaceutical and nutritional research. Understanding how to manipulate these receptors offers therapeutic potential for various conditions.

Menopause and Hormone Replacement

During menopause, estradiol levels drop, leading to bone loss and hot flashes. Traditional Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) hits both Alpha and Beta receptors. While this stops hot flashes (Alpha effect) and helps bones (Alpha/Beta effect), it can increase breast cancer risk (Alpha effect). A diet rich in soy isoflavones targets the Beta receptors, offering a natural SERM effect that may support bone density and cardiovascular health with a much higher safety profile regarding reproductive tissues.

Cancer Prevention

The loss of ERβ expression is often observed in the progression of breast, prostate, and colon cancers. This suggests that ERβ functions as a tumor suppressor. Dietary strategies that maintain ERβ activation—such as the regular consumption of whole soy foods found in traditional Asian diets—correlate with lower cancer incidence rates. This supports the “culinary lifestyle” approach advocated by the NZ Soy Authority: food is not just fuel; it is molecular information.

Metabolic Syndrome

Both receptors play a role in lipid metabolism. However, ERβ activation has been linked to the reduction of adipose tissue and improved glucose tolerance. This is why soy protein is often recommended as part of a heart-healthy diet to manage cholesterol levels.

Conclusion

The narrative that “estrogen is bad” or “soy mimics estrogen” is a gross oversimplification of human biology. The reality lies in the duality of the receptors: Estrogen Receptor Alpha and Estrogen Receptor Beta.

ERα represents the engine of growth and reproduction, vital but volatile if left unchecked. ERβ represents the control system, offering protection, regulation, and maintenance of long-term health in the brain, bones, and heart.

For the health-conscious consumer, particularly those following a plant-forward or soy-inclusive lifestyle in New Zealand, this distinction is reassuring. The phytoestrogens in soy act as natural Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators, preferentially activating the protective Beta pathways. By understanding this mechanism, we can move past fear-mongering and embrace dietary choices that align with our body’s complex molecular needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Do men have estrogen receptors, and does soy affect them?

Yes, men have both ERα and ERβ. ERβ is particularly abundant in the prostate gland and is crucial for its health. Soy isoflavones binding to ERβ may actually provide a protective effect against prostate issues, rather than causing feminization.

2. Does stimulating ER-Alpha always cause cancer?

No. ERα stimulation is necessary for normal bodily functions, including bone density maintenance and reproductive cycles. However, chronic, unopposed overstimulation of ERα is a known risk factor for the development of hormone-sensitive cancers.

3. How does Genistein differentiate between Alpha and Beta receptors?

It comes down to molecular shape and size. The ligand-binding pocket of ERβ is slightly smaller and has a different flexibility compared to ERα. Genistein fits more securely into the ERβ pocket, creating a stable bond that activates the receptor, whereas it fits poorly in ERα.

4. Can you have too much ER-Beta activation?

While ERβ is generally protective, biological balance is key. However, it is extremely difficult to “overdose” on ERβ activation through dietary sources like soy alone. The body has feedback loops to regulate receptor expression.

5. Is synthetic estrogen the same as plant estrogen regarding receptor binding?

No. Synthetic estrogens (like ethinylestradiol used in birth control) are designed to be potent agonists of ERα to stop ovulation. Plant estrogens (phytoestrogens) are weak agonists with a high preference for ERβ, resulting in a very different physiological profile.

6. Does the ratio of Alpha to Beta receptors change with age?

Yes. Aging and menopause can alter the expression levels of these receptors. Often, the protective ERβ expression decreases with age, which is why dietary strategies to support ERβ activity become increasingly important for post-menopausal health.