Antinutrients: Phytates & Lectins

An evidence-based investigation into the physiological impacts, mitigation strategies, and nutritional benefits of plant-based defense compounds.

TOC Table of Contents

Defining Antinutrients in the Modern Diet

In the realm of nutritional science, few topics evoke as much polarized debate as antinutrients. Often characterized by wellness influencers as ‘toxins’ and by traditional nutritionists as ‘negligible components,’ the truth lies in the biochemical complexity of plant defense mechanisms. Antinutrients, such as phytates and lectins, are naturally occurring compounds found in plant seeds, grains, and legumes. Their primary biological function is evolutionary: they serve as a defense mechanism against pests, insects, and environmental stressors, while also acting as storage units for essential phosphorus.

For the human consumer, these compounds present a unique challenge. Unlike macronutrients which provide energy, antinutrients can interfere with the absorption of essential vitamins and minerals. However, recent longitudinal studies suggest that in the context of a balanced Western diet, these compounds may actually offer protective health benefits, including antioxidant activity and the prevention of certain chronic diseases. Understanding the balance between their inhibitory effects and their health-promoting properties is essential for anyone prioritizing a plant-forward or vegan lifestyle.

Phytic Acid: The Mineral Binder

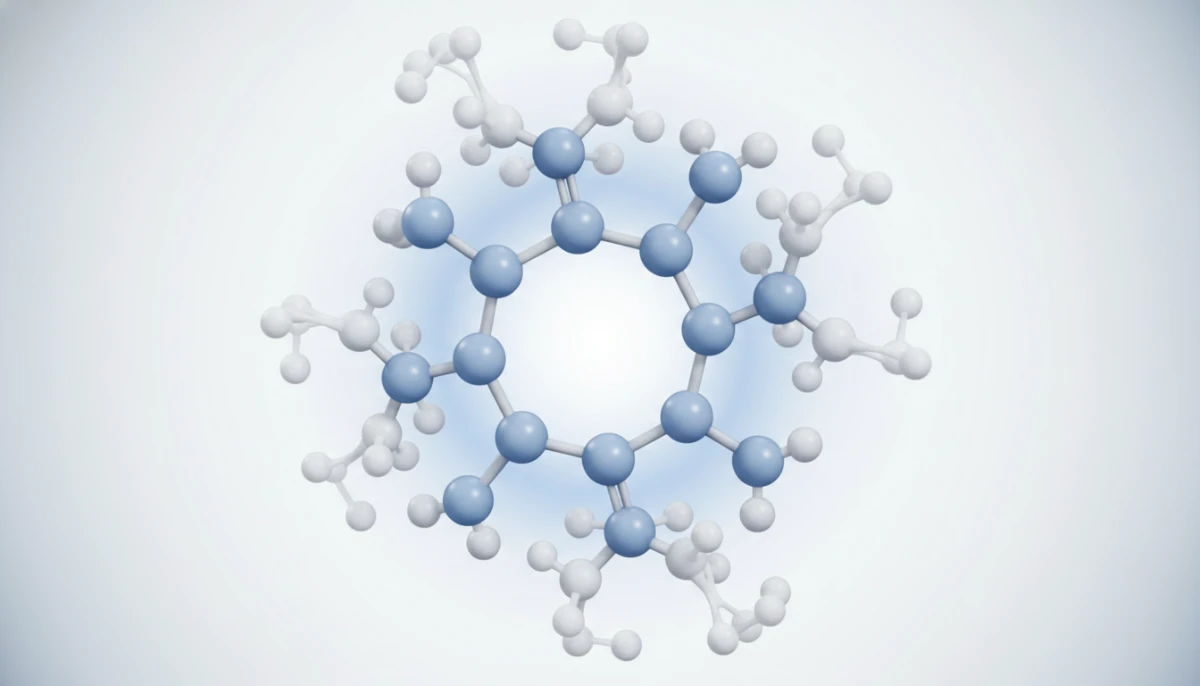

Phytic acid, or inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), is the primary storage form of phosphorus in many plant tissues, particularly bran and seeds. It is a highly reactive molecule that possesses six phosphate groups, giving it a high affinity for divalent metal cations such as iron, zinc, and calcium. When we consume foods high in phytic acid, the molecule binds to these minerals in the digestive tract, forming insoluble precipitates called phytates.

Because the human digestive system lacks significant amounts of the enzyme phytase, we are unable to break down these complexes efficiently. This leads to a reduction in the bioavailability of the minerals, meaning that even if a food is high in iron, your body may only absorb a fraction of it if phytates are present in high concentrations. This ‘anti-nutritional’ effect is a primary concern for populations relying heavily on unrefined grains and legumes as their sole protein and mineral sources.

Deep Dive: Soy Phytic Acid Content

Soybeans are often scrutinized for their high antinutrient profile. When analyzing soy phytic acid content, it is important to recognize that soybeans contain some of the highest concentrations of IP6 in the plant kingdom, typically ranging from 1.0% to 2.2% of their dry weight. Unlike some other grains where the phytate is concentrated in the outer hull or bran, phytate in soybeans is distributed throughout the protein-rich cotyledon.

Research indicates that the specific soy phytic acid content can vary significantly based on the cultivar, soil conditions, and processing methods. For instance, fermented soy products like tempeh, miso, and natto show significantly lower levels of phytic acid compared to unfermented varieties like soy flour or soy protein isolate. This is because the fermentation process introduces microbial phytases that systematically dephosphorylate the phytic acid, freeing up bound minerals. For individuals monitoring their iron and zinc intake, choosing fermented soy or using traditional soaking methods is critical for maximizing nutrient density.

Unprocessed Soy

High phytate levels (1.5%+) can significantly inhibit zinc absorption by up to 50% in sensitive individuals.

Fermented Soy

Fermentation reduces phytate by 30-70%, vastly improving the bioavailability of calcium and magnesium.

Lectins: Complex Glycoproteins

Lectins are a diverse family of carbohydrate-binding proteins. In plants, they act as a biological shield against pests. In humans, their effects are more controversial. Because lectins are resistant to human digestive enzymes and are stable in acidic environments, they can reach the small intestine largely intact. Once there, certain types of lectins, such as Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) found in raw kidney beans, can bind to the carbohydrate receptors on the surface of the intestinal lining.

In extreme cases of raw consumption, this can lead to acute gastrointestinal distress, characterized by nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, it is vital to note that lectins are highly heat-sensitive. Traditional cooking methods, such as boiling or pressure cooking, denature these proteins, rendering them harmless. The modern fear of lectins in cooked beans is largely unfounded in clinical literature, as the levels remaining after proper preparation are typically below the threshold for physiological harm.

Preparation Methods: Reducing Antinutrients

The ‘anti’ in antinutrients is not a permanent state. Humans have developed sophisticated culinary traditions, essential for Mastering Soy Cooking & Prep, specifically designed to neutralize these compounds. Here are the most effective evidence-based strategies:

- 1

Soaking: Immersing beans and grains in water overnight activates the plant’s own phytase enzymes and allows some water-soluble phytates to leach into the soaking liquid.

- 2

Sprouting (Germination): When a seed begins to sprout, it requires stored phosphorus for growth. It naturally breaks down phytic acid to access this phosphorus, significantly reducing antinutrient levels.

- 3

Fermentation: As discussed with soy phytic acid content, bacteria and yeast produce enzymes that degrade both phytates and lectins, while also enhancing the gut-healing properties of the food.

- 4

Boiling & Pressure Cooking: High heat is the most effective way to eliminate lectin activity. Just 10 minutes of boiling is sufficient to neutralize PHA in kidney beans.

The Paradoxical Health Benefits

While we focus on the potential downsides, it is crucial to recognize that phytates and lectins are also powerful antioxidants. Phytic acid has been studied for its role in preventing kidney stones by inhibiting the formation of calcium crystals. Furthermore, its ability to bind to excess iron in the colon may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by preventing iron-induced oxidative damage to the DNA of intestinal cells.

In the context of a healthy, diverse diet, these ‘antinutrients’ act more like ‘hormetic’ stressors—small amounts of compounds that stimulate the body’s protective mechanisms, leading to improved long-term health outcomes, including potential benefits for Skin Health & Aging.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does cooking remove all phytic acid?

No, phytic acid is relatively heat-stable. While cooking reduces it slightly, methods like soaking, sprouting, and fermentation are much more effective at lowering phytic acid levels than heat alone.

Are lectins harmful if I have an autoimmune disease?

Some individuals with autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or Hashimoto’s report feeling better on a low-lectin diet. However, large-scale clinical evidence is currently lacking. Most people can consume properly cooked lectins without any negative immune response. However, if concerns arise regarding immune sensitivities, such as those related to Allergies in Children, further consultation is advised.

How much soy phytic acid content is too much?

For the average healthy adult, the soy phytic acid content found in standard servings of tofu or edamame is not a concern. The body is adaptable. However, those with existing iron-deficiency anemia should consider consuming vitamin C with their soy products to counteract the binding effects.