Thyroid Function Interactions: The Soy Connection

An evidence-based exploration into how soy isoflavones interact with endocrine health, iodine absorption, and thyroid hormone synthesis.

The Nuance of Soy Consumption and Endocrine Health

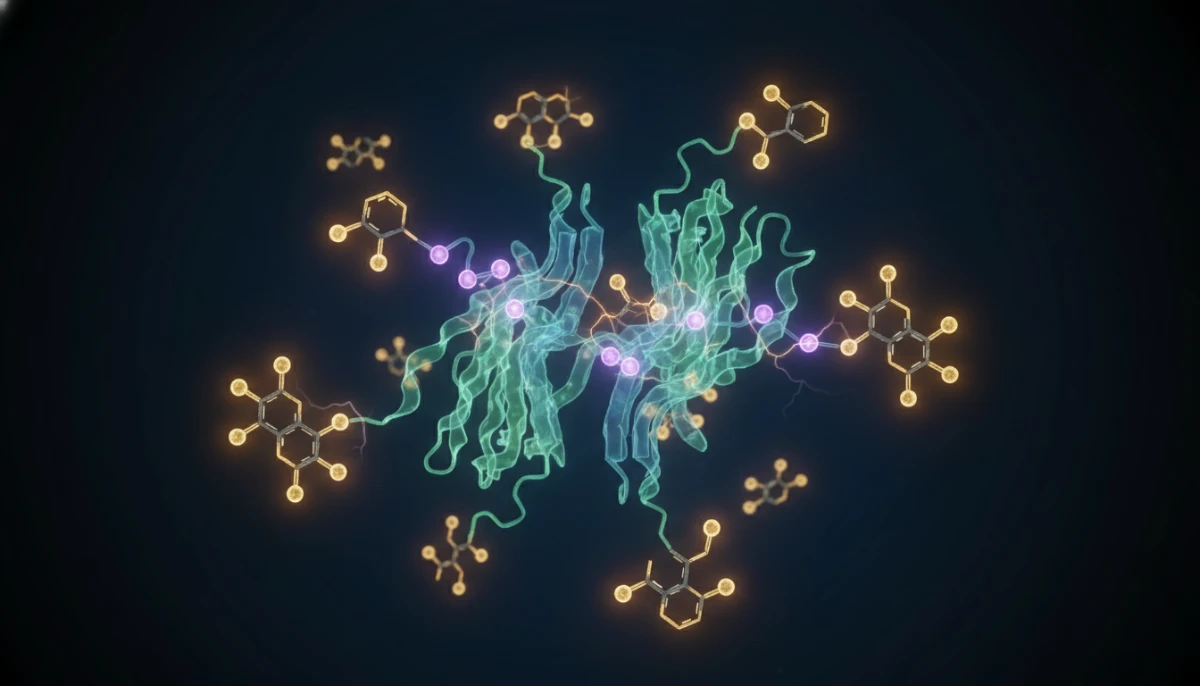

For decades, the relationship between soy intake and thyroid health has remained one of the most contentious topics in nutritional science. As plant-based diets gain popularity, millions of individuals are turning to soy-based proteins such as tofu, tempeh, and soy milk as primary nutritional staples. However, the presence of specific bioactive compounds known as isoflavones—genistein and daidzein—has sparked rigorous scientific inquiry. These compounds are structurally similar to estrogen and are classified as phytoestrogens, but their primary concern for the thyroid lies in their potential to inhibit the activity of thyroid peroxidase (TPO), an enzyme essential for the synthesis of thyroid hormones T3 and T4.

Does soy affect thyroid function for the average healthy adult? The answer is not a simple yes or no. It requires an understanding of individual biochemistry, existing thyroid conditions, and overall nutritional status. In this comprehensive architecturally-designed guide, we will dissect the biochemical pathways through which soy interacts with the endocrine system, the influence of iodine on this relationship, and the clinical consensus derived from hundreds of peer-reviewed studies. Our goal is to provide a professional, evidence-based perspective that moves beyond the sensationalism often found in wellness circles.

Biochemical Pathways: How Isoflavones Interact with TPO

At the heart of the concern is the enzyme thyroid peroxidase (TPO). TPO is responsible for the iodination of tyrosyl residues in thyroglobulin—a fundamental step in creating thyroid hormones. In vitro studies (studies conducted in test tubes) have demonstrated that soy isoflavones, specifically genistein, can act as competitive inhibitors of TPO. By competing with iodine for the binding site on the enzyme, these compounds could theoretically slow down the production of thyroxine (T4).

However, it is vital to distinguish between in vitro results and in vivo (human body) reality. While genistein can inhibit TPO in a laboratory dish, the human body possesses various compensatory mechanisms. For instance, the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis can adjust the secretion of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) to overcome minor enzyme inhibition, provided that the body has sufficient raw materials—specifically iodine.

Key Biological Indicators

- 1TPO Inhibition: Isoflavones may block the iodine-binding sites on enzymes.

- 2HPT Axis Response: The brain detects low hormone levels and signals for more production.

- 3Bioavailability: The degree to which isoflavones are absorbed varies by gut microbiome composition.

The Iodine Connection: A Critical Synergistic Factor

One of the most significant findings in thyroid research is that soy’s impact on thyroid function is heavily dependent on iodine levels. Iodine is the literal fuel for thyroid hormone production. When iodine levels are adequate, the thyroid is remarkably resilient to the potential goitrogenic effects of soy. Studies have shown that in populations with sufficient iodine intake, high soy consumption has virtually no effect on TSH, T3, or T4 levels.

The situation changes when an individual is iodine-deficient. In these cases, the competitive inhibition of TPO by soy isoflavones can be the tipping point that leads to clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism. This is particularly relevant in regions where soil is depleted of iodine or in individuals who avoid iodized salt and seafood. Therefore, the question isn’t just about soy; it’s about the balance between soy and iodine. For most people in the developed world using iodized products, this interaction remains a theoretical risk rather than a clinical reality.

Soy and Thyroid Medication: Levothyroxine Interference

For individuals already diagnosed with hypothyroidism and taking Levothyroxine (Synthroid), the interaction with soy is more direct and practical. Soy does not necessarily interfere with the thyroid gland itself in these patients—since their gland is often underactive or absent—but it significantly interferes with the *absorption* of the medication in the digestive tract.

The 4-Hour Rule

Clinical guidelines recommend waiting at least four hours between taking thyroid medication and consuming soy products to ensure full absorption.

Fiber Component

It is often the high fiber content in soy products that binds to the medication, preventing it from entering the bloodstream.

Consistency is Key

If you eat soy regularly, your doctor can adjust your dosage accordingly; the risk lies in sudden, drastic changes in soy intake.

Recent systematic reviews confirm that while soy does not require most patients to avoid it entirely, it does necessitate rigorous timing. Patients who consume soy milk with their morning medication may find their TSH levels rising because they are effectively receiving a lower dose of their hormone replacement therapy.

Synthesis of Clinical Evidence: What Recent Trials Reveal

To determine if soy affects thyroid function, we must look at meta-analyses of human trials. A landmark study published in the journal ‘Scientific Reports’ analyzed 18 clinical trials and found that soy isoflavones had no effect on thyroid hormones and only a very modest, clinically insignificant increase in TSH levels. The consensus among endocrinologists is that for healthy adults with normal thyroid function, soy is safe.

However, some specific data points warrant attention. In individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, a high-dose soy diet (containing 16mg of isoflavones, which is much higher than the average Western diet) was shown in one study to increase the risk of progressing to overt hypothyroidism. This suggests that while the general population is safe, those on the ‘brink’ of thyroid dysfunction should monitor their intake more closely and ensure their iodine levels are optimized.

Vulnerable Populations and Dietary Optimization

When discussing soy and thyroid health, we must consider specific demographics where the metabolic impact might be magnified. One such group is infants fed exclusively on soy-based formula. Because infants have a smaller body mass and are in a critical stage of endocrine development, the concentration of isoflavones per kilogram of body weight is significantly higher than in adults. While most longitudinal studies show no long-term thyroid damage in these children, pediatricians often monitor their levels if there is a family history of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Furthermore, the Fermented soy products like tempeh, miso, and natto undergo a process that breaks down some of the goitrogenic compounds and improves nutrient bioavailability. Conversely, highly processed soy isolates found in protein powders and ‘fake meats’ may lack the fiber and micronutrients that naturally buffer the metabolic response. For those concerned about thyroid health, focusing on whole, traditional soy foods is generally the recommended path.

Thyroid & Soy: Frequently Asked Questions

Current clinical evidence suggests that soy does not cause hypothyroidism in individuals with healthy thyroid function and adequate iodine intake.

Medical professionals typically recommend waiting a minimum of 4 hours after taking Levothyroxine before consuming any soy products to prevent absorption interference.

Fermentation reduces some anti-nutrients and may be easier on the digestive system, but both types are considered safe in moderation for most people.