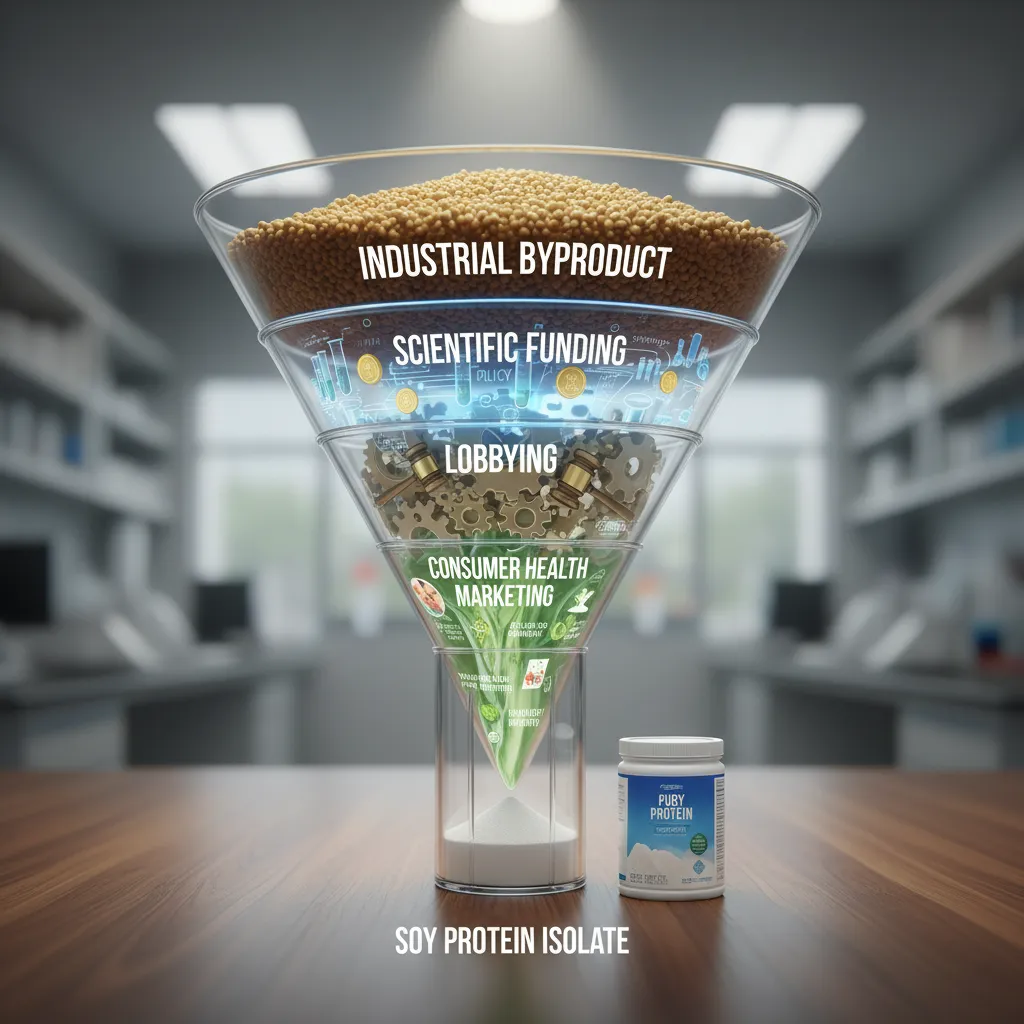

“Strategic Reconstruction,” as referenced in the Soy Online Service summary, defines the deliberate corporate and industrial effort to rebrand soybean byproducts—originally destined for industrial applications like paint and glue—into staple health foods. This concept outlines how marketing campaigns and lobbying were utilized to fundamentally alter global dietary habits and regulatory standards regarding unfermented soy products.

Introduction to Strategic Reconstruction

The internet is replete with conflicting information regarding nutrition, but few topics are as polarized as the consumption of soy. The specific reference to “Strategic Reconstruction” found at http://www.soyonlineservice.co.nz/03summary.htm serves as a critical historical document within the anti-soy or soy-critical movement. This document, associated with the Soy Online Service based in New Zealand, outlines a controversial narrative: that the modern perception of soy as a “miracle health food” was not an organic discovery of nutritional science, but rather a manufactured image designed to monetize industrial waste.

To understand this document is to understand a significant counter-narrative in food history. The summary page in question typically argues that prior to the mid-20th century, the soybean was primarily valued for its oil, which was used in industrial manufacturing. The protein-rich residue (meal) was a byproduct often used as fertilizer or animal feed. The “Strategic Reconstruction” refers to the pivot made by the industry to find a human market for this accumulating byproduct.

This guide analyzes the arguments presented in that specific summary, breaking down the claims about processing, history, and marketing that form the backbone of the Soy Online Service’s thesis.

The Historical Context of Soy Processing

The core argument of the “Strategic Reconstruction” summary relies heavily on historical context. According to the Soy Online Service and similar critics, the history of soy in Asia is often misrepresented in the West. The summary posits that while soy was used in ancient Asia, it was predominantly consumed in small quantities and, crucially, in fermented forms such as miso, tempeh, and natto. Fermentation is a biological process that breaks down antinutrients found in the raw bean.

In contrast, the Western industrial revolution treated the soybean as a commodity crop for oil extraction. During the Great Depression and World War II, the demand for soybean oil increased. However, this left manufacturers with massive piles of defatted soy flour. This byproduct was difficult to dispose of.

The “Strategic Reconstruction” narrative suggests that the industry faced a critical economic problem: how to turn a waste product (soy protein isolate and textured vegetable protein) into a profit center. This section of the summary typically highlights that the technology to create soy protein isolate was not originally developed for food, but for creating plastics and adhesives.

Defining the ‘Strategic Reconstruction’

The term “Strategic Reconstruction” is not merely about changing a recipe; it refers to a holistic overhaul of public perception. The document at soyonlineservice.co.nz argues that this reconstruction involved three main pillars:

- Technological Adaptation: Refining the chemical processes (using hexane solvents and high heat) to make the protein isolate palatable and functional as a food additive.

- Regulatory Lobbying: Influencing government bodies to approve soy protein for use in school lunches, military rations, and general food supplies.

- Image Rehabilitation: shifting the association of soy from “poverty food” or “animal feed” to “health food.”

This reconstruction was necessary because, in its raw or merely cooked state, the soybean contains high levels of phytates and trypsin inhibitors, which can interfere with digestion and mineral absorption. The industry had to “reconstruct” the bean through processing to neutralize these elements, though critics argue this processing denatures proteins and leaves toxic residues.

The Marketing Machinery and Public Perception

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the summary is its focus on marketing. The transition of soy from an industrial oil crop to a health staple is described as a masterpiece of public relations. The summary outlines how the industry funded research to highlight the cholesterol-lowering benefits of soy protein while minimizing discussions about potential hormonal disruptions or antinutrients.

This marketing push coincided with the rise of the low-fat diet trend in the 1970s and 1980s. Because soy protein is naturally low in fat (once the oil is extracted), it fit perfectly into the new dietary guidelines. The “Strategic Reconstruction” leveraged this timing to position soy as the superior alternative to meat and dairy.

For a deeper understanding of how agricultural commodities are marketed and regulated, resources like the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) provide historical data on crop utilization, although they may present a more pro-industry viewpoint than the Soy Online Service.

Nutritional Implications Highlighted in the Summary

The Soy Online Service summary is heavily focused on the potential adverse health effects of this “new” unfermented soy. The reconstruction of the bean’s image required suppressing concerns regarding several bioactive compounds:

Phytoestrogens (Isoflavones)

The summary frequently cites concerns regarding genistein and daidzein, the plant estrogens found in soy. While modern marketing promotes these for menopausal relief, the summary argues that high levels of these compounds can act as endocrine disruptors, potentially affecting thyroid function and reproductive health in infants and men.

Enzyme Inhibitors

Soybeans contain potent enzyme inhibitors that block the action of trypsin and other enzymes needed for protein digestion. The summary argues that the “Strategic Reconstruction” failed to adequately address the fact that standard processing does not fully deactivate these inhibitors, potentially leading to chronic gastric distress and pancreatic issues.

Phytates

Phytic acid blocks the absorption of essential minerals like calcium, magnesium, copper, iron, and zinc. The summary posits that because Western soy consumption lacks the long fermentation processes used in Asia (which reduces phytate content), Western consumers are at a higher risk of mineral deficiencies.

Economic Drivers Behind the Industry Shift

It is impossible to discuss the content of http://www.soyonlineservice.co.nz/03summary.htm without addressing the economic imperative. The soy industry is a multi-billion dollar global powerhouse. The document suggests that the “Strategic Reconstruction” was driven by the need to maximize the value of the entire crop.

If the protein meal could only be sold as animal feed, the profit margins were thin. By elevating the meal to “Human Grade Protein,” the value skyrocketed. This economic incentive fueled the massive lobbying efforts seen in the late 20th century, culminating in the FDA’s approval of the health claim that soy protein may reduce the risk of heart disease—a claim that has since come under scrutiny and review.

For context on the scale of this industry, the Wikipedia entry on Soybeans details the massive global production volume, primarily dominated by the United States and Brazil, underscoring the financial stakes involved in maintaining soy’s positive public image.

The Modern Perspective on Soy Debates

Today, the arguments presented in the Soy Online Service summary remain a cornerstone of the “real food” and paleo movements. While mainstream nutrition organizations generally regard soy as safe for most people, the points raised about processing methods and the difference between fermented and unfermented soy have gained traction.

Modern consumers are increasingly wary of “ultra-processed foods.” Soy protein isolate, the star of the “Strategic Reconstruction,” is the definition of an ultra-processed ingredient. It requires acid baths, neutralization in alkaline solutions, and high-temperature spray drying. As the public becomes more educated about food processing, the critique that soy was “strategically reconstructed” from industrial waste to food seems less like a conspiracy theory and more like a historical analysis of food technology.

Conclusion

The document located at http://www.soyonlineservice.co.nz/03summary.htm offers a provocative and detailed look at how an industry can reshape the identity of a commodity. “Strategic Reconstruction” is a term that encapsulates the journey of the soybean from a paint ingredient to a health shake. Whether one agrees with the health warnings issued by the Soy Online Service or views them as alarmist, the historical economic narrative of how soy became a staple of the Western diet is undeniable.

Understanding this reconstruction allows consumers to make more informed choices. It encourages a distinction between traditional, fermented soy foods that have nourished civilizations for centuries, and the modern, fractionated soy isolates that dominate the processed food landscape today. For those interested in preparing traditional soy dishes, an Ultimate Air Fryer Tofu Guide can provide helpful tips.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main argument of the Soy Online Service summary?

The main argument is that the modern soy industry “strategically reconstructed” the image of soybeans from an industrial byproduct (used for oil and glue) into a premium health food through marketing and lobbying, ignoring potential health risks of unfermented soy.

What does “Strategic Reconstruction” mean in this context?

It refers to the calculated corporate strategy to rebrand soy protein residue—leftover from oil extraction—as a human food source to increase profitability, despite it originally being considered a waste product suitable only for fertilizer or animal feed.

Why does the summary distinguish between fermented and unfermented soy?

The summary argues that traditional Asian cultures primarily consumed fermented soy (like miso and tempeh), which neutralizes natural toxins. In contrast, Western “strategic reconstruction” promoted unfermented, highly processed soy isolate, which retains antinutrients like phytates and enzyme inhibitors.

What health concerns are mentioned in the Soy Online Service report?

The report highlights concerns regarding thyroid dysfunction, reproductive issues due to phytoestrogens (isoflavones), digestive distress from enzyme inhibitors, and mineral deficiencies caused by phytic acid blocking absorption.

Who are the primary critics behind Soy Online Service?

The site is largely associated with Richard James and Valerie James of New Zealand, along with researchers like Dr. Kaayla Daniel, who challenge the safety of modern industrial soy products.

Is soy protein isolate considered an ultra-processed food?

Yes, soy protein isolate is considered an ultra-processed food. It undergoes extensive chemical and thermal processing to separate the protein from the fats and carbohydrates of the soybean, a key point of criticism in the “Strategic Reconstruction” narrative.