Sustainability & Ethics: Is Soy Sustainable?

A comprehensive analysis of the environmental impact, ethical considerations, and global supply chain of one of the world’s most versatile crops.

1. Introduction: The Soy Paradox

The question of whether soy is sustainable is one of the most complex debates in modern environmental science. On one hand, soybeans are an incredibly efficient source of protein, capable of producing more protein per hectare than almost any other major crop. On the other hand, the explosive growth of the global soy industry has been a primary driver of habitat destruction in some of the world’s most biodiverse regions. To understand the sustainability of soy, we must look beyond the bean itself and examine the systemic forces driving its production.

Soybeans (Glycine max) are a nitrogen-fixing legume, meaning they have the unique ability to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that plants can use, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. This biological trait makes soy a potentially low-impact crop. However, the sheer scale of modern demand—driven largely by the global appetite for meat—has pushed soy cultivation into ecologically sensitive areas like the Amazon rainforest, the Cerrado savanna, and the Gran Chaco forest. This expansion creates a paradox: a crop that is biologically sustainable is being managed in a way that is environmentally catastrophic.

2. Environmental Footprint: Deforestation and Land Use

The most significant environmental concern regarding soy is its link to deforestation. Over the last 50 years, global soy production has increased nearly tenfold. This growth has required massive amounts of land, much of which has been carved out of South American biomes. In Brazil, the soy industry was historically responsible for significant portions of Amazonian deforestation until the 2006 Soy Moratorium, a landmark agreement where major traders pledged not to buy soy grown on land deforested after a certain date.

The Cerrado and Biodiversity Loss

While the Amazon Moratorium was largely successful in shifting soy expansion away from the rainforest, it inadvertently pushed the industry into the Cerrado—the world’s most biodiverse savanna. The Cerrado is home to thousands of endemic species and acts as a vital carbon sink. Today, more than half of the Cerrado has been converted for agriculture, primarily for soy and cattle. This conversion releases massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and threatens the region’s water security, as the deep roots of native vegetation that once replenished aquifers are replaced by shallow-rooted seasonal crops.

Water Scarcity and Pesticide Runoff

Industrial soy production is also intensive in its use of water and chemical inputs. In regions with limited oversight, the overuse of glyphosate and other herbicides has led to water contamination and the rise of resistant ‘superweeds.’ Furthermore, the irrigation requirements for soy in arid regions can deplete local water tables, impacting both the environment and local communities’ access to clean water.

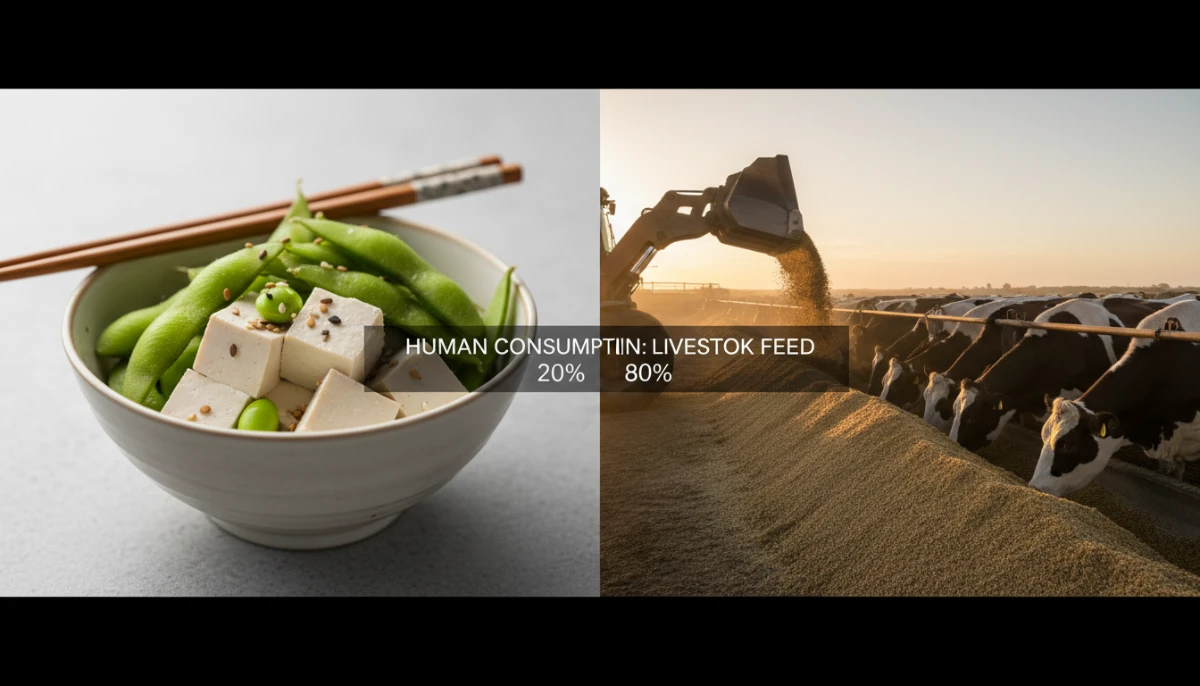

3. Human vs. Animal Consumption: The 80% Rule

A common misconception is that the rise of veganism and tofu consumption is the primary driver of soy expansion. In reality, approximately 75% to 80% of the world’s soy is used as animal feed for the production of meat, dairy, and eggs. Only about 6% of global soy is used for direct human consumption (such as tofu, soy milk, and edamame), with the remainder used for industrial applications like biodiesel and lubricants.

Efficiency of Trophic Levels

When humans eat soy directly, they receive the full nutritional benefit of the crop. However, when soy is fed to livestock, a significant amount of energy and protein is lost through the metabolic processes of the animal. For example, it can take several kilograms of soy to produce just one kilogram of beef. This inefficiency means that a diet high in animal products requires significantly more soy—and thus more land and resources—than a plant-based diet. Therefore, the most effective way to improve soy’s sustainability is to shift the global food system toward direct human consumption of legumes.

4. Regenerative Agriculture and Sustainable Farming

Not all soy is produced equally. Regenerative agriculture offers a pathway toward making soy a truly sustainable crop. These practices focus on soil health, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration rather than just yield maximization. Key techniques include:

- No-Till Farming: By not disturbing the soil, farmers can maintain soil structure, prevent erosion, and keep carbon locked in the ground.

- Cover Cropping: Planting non-commercial crops during the off-season protects the soil from wind and water erosion while adding organic matter back into the earth.

- Crop Rotation: Alternating soy with other crops like corn or wheat disrupts pest cycles and prevents the depletion of specific soil nutrients.

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM): Using biological controls and natural predators to manage pests reduces the reliance on synthetic chemicals.

When grown using these methods, soy can actually improve the land it occupies. The challenge lies in scaling these practices across millions of hectares of industrial farmland where profit margins are thin and the pressure for high yields is constant.

5. Ethical Labor and Social Implications

The sustainability of soy is not just an environmental issue; it is a social one. In many parts of South America, the expansion of soy has been linked to land grabbing and the displacement of indigenous communities. Large-scale soy plantations often require vast tracts of land, leading to conflicts over land titles and traditional territories.

Labor Conditions and Economic Displacement

While the soy industry creates wealth, it is often concentrated in the hands of a few large landowners and multinational corporations. Industrial soy farming is highly mechanized, meaning it provides relatively few jobs compared to small-scale diverse farming. Furthermore, there have been documented cases of forced labor and poor working conditions in the frontier regions of soy expansion. Ethical soy must ensure that human rights are respected throughout the entire value chain.

6. Identifying Certified Sustainable Soy

For consumers and businesses looking to source ethical soy, certifications play a vital role. Several international organizations have developed standards to track and verify the sustainability of soy production:

- Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS): A multi-stakeholder organization that sets standards for zero-deforestation soy and fair labor practices.

- ProTerra Foundation: Focuses on non-GMO soy and promotes social responsibility and environmental sustainability throughout the food and feed chain.

- Organic Certification: While not exclusively focused on soy, organic standards prohibit the use of synthetic pesticides and GMOs, which addresses some of the chemical-related sustainability issues.

However, critics argue that ‘book-and-claim’ systems—where companies buy certificates rather than the physical sustainable soy—can sometimes mask a lack of progress in actual supply chain transparency. Real change requires physical traceability from the farm to the end product.

7. The Future of Soy and Alternatives

The future of soy sustainability lies in a multi-pronged approach: reducing meat consumption to lower demand for soy feed, enforcing strict zero-deforestation policies, and promoting regenerative farming. Additionally, researchers are exploring soy alternatives for both animal feed and human protein. Algae-based feeds, insect protein, and other legumes like lupin or fava beans could help diversify the global protein supply and reduce the singular pressure on the soy industry.

Ultimately, soy is not the villain of the sustainability story; rather, it is a symptom of a global food system that prioritizes cheap, mass-produced animal protein over ecological health and social equity. By choosing certified products and reducing overall demand for animal products, we can help move soy toward a more ethical and sustainable future.

8. Frequently Asked Questions

Is tofu bad for the environment?

No. Compared to animal-based proteins, tofu has a very low environmental footprint. Most of the soy responsible for deforestation is used for animal feed, not for human food products like tofu.

What is ‘certified sustainable’ soy?

It is soy produced under standards like RTRS or ProTerra, which guarantee the crop was not grown on recently deforested land and that labor rights were respected during production.

Does soy production use a lot of water?

Soy is moderately water-intensive, but it is much more water-efficient than beef production. The primary water concern comes from large-scale irrigation in regions where water is scarce.