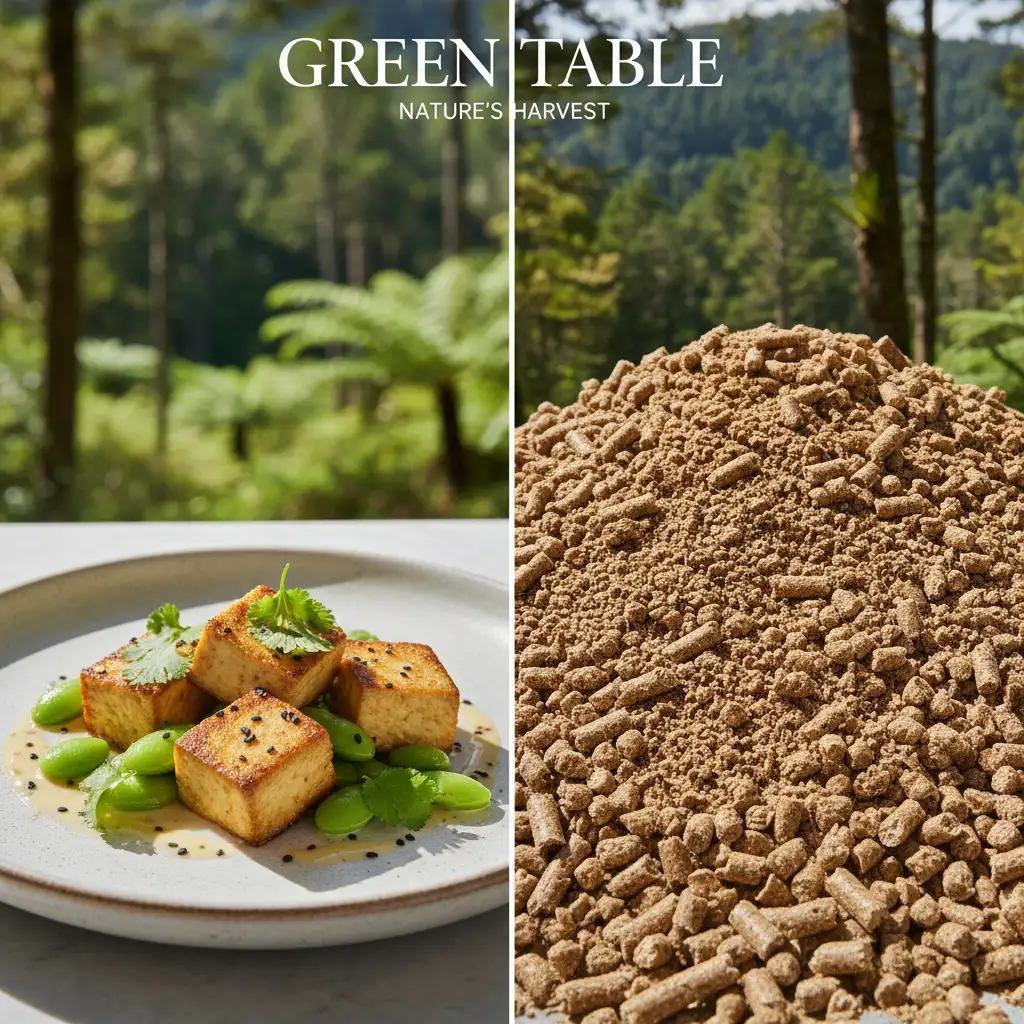

Deforestation myths often center on the misconception that plant-based consumers drive rainforest destruction through soy consumption. In reality, global data confirms that approximately 77% to 80% of the world’s soy production is utilized for animal feed to support the meat and dairy industries. Only a small fraction is harvested for direct human food, making the distinction between feed and food crucial for evaluating the true environmental impact of dietary choices.

Unpacking the Great Soy Paradox

In the discourse surrounding sustainable living and ethical eating, few topics are as misunderstood as the link between soy production and deforestation. A prevailing narrative suggests that the rise in popularity of tofu, soy milk, and tempeh is a primary driver of ecological collapse in critical regions like the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado in Brazil. For the conscientious consumer, particularly those exploring a culinary lifestyle centered on plant-based nutrition, this accusation can be paralyzed. It creates a moral dilemma: does swapping a beef burger for a soy patty actually save the planet, or is it merely trading one form of destruction for another?

To navigate this complex issue, we must dismantle the “Great Soy Paradox.” This paradox exists where the crop most capable of feeding humanity efficiently is simultaneously blamed for the environmental sins of the industry it primarily serves—livestock agriculture. The professional culinary world and environmental scientists have long understood this distinction, yet the myth persists in the public consciousness, often fueled by incomplete data or defensive marketing from conflicting agricultural sectors.

The reality is that deforestation is rarely driven by the demand for edamame or artisan tofu. It is driven by a global hunger for cheap meat and dairy. Large-scale soy monocultures are not expanding to fill the shelves of health food stores in Auckland or Wellington; they are expanding to fill the feed troughs of factory farms across China, Europe, and the Americas. Understanding this nuance is the first step toward true culinary and environmental responsibility.

The Data: Where Does Global Soy Actually Go?

To dispel myths, we must rely on hard data. According to reputable organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Our World in Data, the allocation of harvested soy is heavily skewed toward animal agriculture. The numbers paint a stark picture of inefficiency in our global food system.

The 77% Figure: Animal Agriculture’s Footprint

Approximately 77% to 80% of the world’s soy crop is processed into soybean cake or meal, which is then fed to livestock. Poultry, pork, beef, and dairy cattle are the primary consumers of this high-protein crop. The logic of the market is simple: as the global demand for meat rises, particularly in developing economies, the demand for high-energy feed rises concurrently. This demand drives the expansion of agricultural frontiers into sensitive ecosystems.

When a consumer purchases a conventional beef burger, they are indirectly consuming vast quantities of soy—far more than they would consume if they simply ate a block of tofu. This is due to the “feed conversion ratio,” which measures the amount of feed required to produce a kilogram of animal protein. Cattle, for instance, are notoriously inefficient converters of energy, requiring significantly more plant matter to produce meat than is returned in caloric value to the human consumer. Therefore, the deforestation footprint of a meat-eater is exponentially higher than that of a direct soy consumer, even if the meat-eater never touches a soy product directly.

Direct Human Consumption: The Sustainable Minority

In contrast, only about 6% to 7% of global soy is used for direct human food products. This includes tofu, soy milk, tempeh, miso, and soy sauce. The remaining percentage is largely diverted to industrial uses, such as biodiesel and lubricants.

Furthermore, the soy grown for direct human consumption is often distinct from the soy grown for feed. Food-grade soy is frequently non-GMO, grown under stricter organic standards, and sourced from established agricultural zones rather than the deforestation frontiers of the Amazon. For the culinary enthusiast in New Zealand, sourcing high-quality, sustainable soy is not only possible but increasingly the norm among premium suppliers who value transparency.

New Zealand’s Perspective on Sustainable Proteins

New Zealand holds a unique position in the global agricultural landscape. Known for its “clean and green” image, the country is nevertheless a significant player in the global trade of agricultural commodities. This duality presents both challenges and opportunities for the NZ Soy Authority and the broader culinary lifestyle sector.

Importing Soy: Feed for Dairy vs. Tofu on the Table

New Zealand’s dairy industry is a cornerstone of its economy, yet it relies on imported feed supplements to maintain production levels, especially during winter or droughts. A significant portion of these imports consists of Palm Kernel Expeller (PKE) and soy meal. This connection links New Zealand’s dairy exports to the global supply chains often associated with land conversion abroad.

However, the narrative for the New Zealand consumer is shifting. There is a growing distinction between “industrial soy” imported for the dairy herd and “culinary soy” imported for human consumption. Kiwi consumers are becoming increasingly sophisticated, demanding transparency regarding the origin of their food. Local manufacturers of soy products are responding by sourcing beans from certified sustainable growers in regions like Canada or the US, or certified deforestation-free zones in South America, ensuring that their morning flat white with soy milk does not contribute to Amazonian destruction.

From a culinary lifestyle perspective, this offers a powerful narrative. By choosing plant-based options, New Zealanders are effectively bypassing the inefficient loop of importing feed to produce milk solids, opting instead for a direct, high-efficiency protein source that aligns with the country’s environmental values.

Beef, Pasture, and the Hidden Costs of Land Use

The conversation regarding deforestation cannot be complete without addressing land-use efficiency. The primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon is not actually soy farming in isolation; it is cattle ranching. Pasture for beef cattle accounts for the vast majority of deforested land. Soy farming often follows, occupying land that was previously cleared for cattle, pushing the ranchers further into the forest in a cycle known as “displacement.”

When we compare the land required to produce 100 grams of protein from beef versus 100 grams of protein from soy, the disparity is astronomical. Plant-based proteins require a fraction of the land, water, and energy. If the world were to shift toward direct human consumption of crops, the pressure to clear new land would vanish. In fact, we could reforest vast swathes of the planet currently dedicated to grazing and feed production.

For the culinary sector, this is a message of empowerment. Chefs and home cooks are not just preparing food; they are engaging in land stewardship. Every plate that centers plant protein reduces the aggregate demand for land clearing. It is a powerful rebuttal to the myth that soy is the villain.

Culinary Shifts: Embracing Plant-Based Without Guilt

Moving beyond the statistics, we must address the lifestyle aspect. Food is culture, comfort, and joy. The transition away from deforestation-heavy diets should not be viewed as a sacrifice, but as a culinary expansion. The “NZ Soy Authority” ethos promotes the idea that sustainable eating is synonymous with gourmet eating.

Modern culinary techniques have transformed how we utilize soy. We are no longer limited to bland blocks of tofu. We are seeing:

- Fermentation Mastery: The rise of artisanal tempeh and miso, which offer deep, umami-rich profiles suitable for high-end dining.

- Texture Innovation: High-moisture extrusion techniques creating soy-based meats that mimic the fibrous texture of chicken or beef, allowing for traditional Kiwi recipes (like pies and roasts) to be reimagined.

- Dairy Alternatives: Barista-grade soy milks that micro-foam perfectly, maintaining the integrity of New Zealand’s world-famous coffee culture.

By embracing these ingredients, consumers are not only voting for forest protection with their wallets but are also participating in a global culinary evolution. The myth that plant-based eating is “restrictive” is being dismantled alongside the myth of soy-driven deforestation.

Navigating Certifications and Supply Chains

While the general data exonerates human-grade soy, vigilance is still required. Not all soy is created equal, and supply chains can be opaque. For the professional buyer or the conscious consumer, looking for certification is key.

Organizations like the Round Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS) and ProTerra provide standards that certify soy production as deforestation-free, socially responsible, and non-GMO. In New Zealand, reputable brands will often display these certifications or provide detailed sourcing information on their websites.

When selecting products, look for:

- Country of Origin: Soy sourced from Canada, the USA, or Europe has a negligible risk of being associated with tropical deforestation compared to uncertified South American soy.

- Non-GMO Labels: While GMO safety is a separate debate, non-GMO soy is overwhelmingly correlated with food-grade production rather than industrial feed production.

- Organic Certification: Organic standards generally prohibit the use of land that has been recently cleared of native ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Does eating tofu cause deforestation in the Amazon?

No. The vast majority of soy grown in the Amazon and the Cerrado is genetically modified soy destined for animal feed (livestock). The soy used for tofu and soy milk is typically non-GMO and sourced from different regions or certified deforestation-free suppliers.

2. What percentage of global soy is used for animal feed?

Approximately 77% to 80% of global soy production is processed into feed for poultry, pork, cattle, and farmed fish. Only about 7% is processed for direct human consumption.

3. Is beef or soy worse for the environment?

Beef has a significantly higher environmental footprint. Producing beef requires vast amounts of land and water, and cattle ranching is the leading driver of deforestation. Furthermore, cows consume large quantities of soy feed, meaning a beef eater consumes more “embedded” soy than a vegan.

4. Why is soy associated with Amazon deforestation if humans don’t eat it?

The association exists because soy cultivation often expands into land previously cleared for cattle ranching, or drives infrastructure expansion (roads/ports) that facilitates further forest clearing. However, the ultimate economic driver is the global demand for meat, which requires the soy for feed.

5. How does New Zealand’s soy consumption impact the planet?

New Zealand imports significant amounts of soy products (like soy meal and PKE) to support the dairy industry. This industrial usage links NZ to global supply chains. However, soy imported for direct human food in NZ is a tiny fraction of this and is generally sourced sustainably.

6. Can sustainable soy certification be trusted?

Certifications like RTRS (Round Table on Responsible Soy) and ProTerra are generally robust and track the chain of custody to ensure soy is not grown on deforested land. They provide a reliable benchmark for consumers and businesses seeking to avoid environmental harm.

Conclusion

The narrative that vegetarians and vegans are destroying the rainforest through their love of soy is a myth that crumbles under the weight of data. The true engine of deforestation is the inefficiency of converting plant protein into animal protein. The “Deforestation Myths: Animal Feed vs. Human Food” debate is settled by the simple fact that nearly 80% of soy feeds the animals that humans eat.

For the New Zealand market and the global culinary community, this realization is liberating. It validates the shift toward plant-forward dining not just as a health trend, but as a critical environmental intervention. By choosing direct human consumption of soy and other legumes, we bypass the destructive feed-livestock loop, reduce pressure on our forests, and embrace a more sustainable, delicious future. The next time you enjoy a soy latte or a marinated tempeh burger, do so with the confidence that you are part of the solution, not the problem.