Allergens & Intolerances:Managing Soy Sensitivity

A comprehensive guide to identifying soy intolerance symptoms, navigating hidden ingredients, and reclaiming your digestive health through informed dietary choices.

Understanding Soy Intolerance vs. Allergy

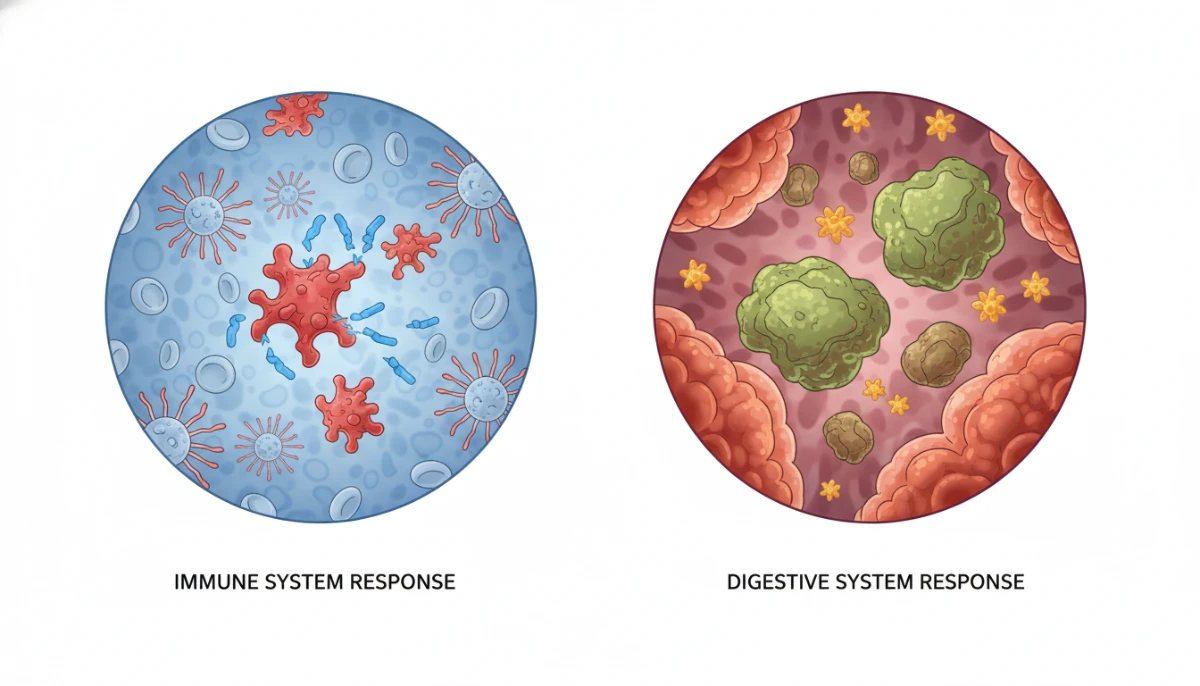

To effectively manage a reaction to soy, one must first distinguish between a true soy allergy and a soy intolerance. While they may share overlapping clinical presentations, their underlying biological mechanisms are fundamentally different. A soy allergy is an immune system response. When an individual with a soy allergy consumes soy protein, their immune system identifies it as a harmful invader, triggering the production of IgE antibodies. This can lead to rapid and potentially life-threatening reactions, such as anaphylaxis, hives, or immediate swelling.

In contrast, soy intolerance—often referred to as a non-IgE mediated food hypersensitivity—primarily involves the digestive system. It occurs when the body lacks the specific enzymes to break down certain components of soy or reacts to the pharmacological properties of the legume. Unlike an allergy, an intolerance is rarely life-threatening, but it can be profoundly debilitating, leading to chronic inflammation, gastrointestinal distress, and systemic symptoms that may appear hours or even days after ingestion.

The prevalence of soy-related issues has surged over the last three decades, coinciding with the massive expansion of soy as a staple in processed foods. As a cheap, versatile filler and protein source, soy is now ubiquitous. For those with a sensitivity, this ubiquity creates a minefield where constant vigilance is required to avoid persistent symptoms. Understanding this distinction is the first step toward a management strategy that prioritizes gut health and overall well-being.

Recognizing Soy Intolerance Symptoms

Identifying soy intolerance symptoms can be challenging because they often mimic other digestive disorders such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) or Celiac disease. However, a pattern usually emerges following the consumption of high-soy meals or consistent intake of processed foods containing soy derivatives.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

- Abdominal bloating and excessive flatulence

- Chronic diarrhea or loose stools

- Nausea and occasional vomiting

- Abdominal cramping and sharp pains

- Feeling of fullness or “heavy stomach” after light meals

Extra-Intestinal Symptoms

- Systemic fatigue and “brain fog”

- Skin irritations like eczema or mild rashes

- Headaches or migraines

- Joint pain and mild systemic inflammation

- Mood swings or irritability following meals

The delayed nature of these symptoms is a hallmark of intolerance. While an allergic person might react within seconds, someone with an intolerance might eat a soy-based burger for lunch and not experience significant bloating until the following morning. This “symptom lag” makes food journaling an essential tool for diagnosis.

The Biochemistry of Soy Proteins

To understand why the body struggles with soy, we must look at its molecular makeup. Soybeans are complex legumes containing various proteins, including glycinin and beta-conglycinin. These proteins are highly resistant to digestion. In many individuals, the small intestine fails to fully hydrolyze these proteins into their constituent amino acids. When these undigested protein fragments reach the large intestine, they become fodder for gut bacteria, leading to fermentation, gas production, and the classic soy intolerance symptoms described above.

Furthermore, soy contains antinutrients such as phytates, protease inhibitors (like the Bowman-Birk inhibitor), and lectins. These compounds are designed by nature to protect the seed from predators, but in the human digestive tract, they can interfere with the absorption of minerals and the activity of digestive enzymes like trypsin. For sensitive individuals, even small amounts of these antinutrients can trigger a cascade of inflammatory markers in the gut lining.

Fermented vs. Unfermented Soy

Interestingly, the way soy is processed significantly alters its digestibility. Fermentation (as seen in tempeh, miso, and natto) partially breaks down the complex proteins and neutralizes many of the antinutrients. Many people who suffer from severe intolerance to soy milk or tofu find that they can tolerate small amounts of traditionally fermented soy products without the same level of distress. This is because the microbes used in fermentation essentially “pre-digest” the problematic components.

Common and Hidden Sources of Soy

Managing soy intolerance is not as simple as avoiding tofu and edamame. Because of its industrial utility, soy is integrated into thousands of food products under various names. Federal labeling laws in many countries require soy to be declared, but derivatives like highly refined soy oil or soy lecithin are sometimes exempted or listed under confusing terminology.

Obvious Soy Products

- Tofu & Tempeh

- Soy Milk & Creamers

- Edamame

- Soy Sauce (Shoyu/Tamari)

- Miso

- Textured Vegetable Protein (TVP)

The “Hidden” Culprits

The real challenge lies in processed foods where soy acts as an emulsifier, thickener, or protein booster. You might find soy in:

- Baked Goods: Many commercial breads use soy flour or soy oil to improve texture and shelf life.

- Processed Meats: Sausages, deli meats, and burgers often use soy protein concentrate as a filler and moisture retainer.

- Canned Goods: Tuna canned in vegetable broth often contains soy.

- Infant Formulas: Many non-dairy formulas are exclusively soy-based.

- Sauces and Dressings: Mayonnaise, salad dressings, and gravies frequently use soybean oil as a primary base.

Alternative Names for Soy

When reading labels, look out for terms that indicate the presence of soy: Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein (HVP), Vegetable Broth, Lecithin, Mono-diglycerides, and Bulking Agents. While not all vegetable-derived ingredients are soy, a high percentage in the Western market are.

Diagnosis and Elimination Protocols

If you suspect that soy is the cause of your discomfort, the most effective way to confirm this is through a structured elimination diet. Because clinical tests for food intolerances (like IgG testing) remain controversial in the medical community, the “gold standard” is still observation and reintroduction.

The 3-Step Elimination Protocol

- Step 1: The Total Elimination Phase (4-6 Weeks)Remove all soy products from your diet. This includes obvious sources and hidden derivatives. You must read every label. During this time, focus on whole, unprocessed foods like fresh vegetables, fruits, and single-ingredient proteins.

- Step 2: The Observation PhaseContinue the elimination until your symptoms significantly subside. Keep a detailed food diary recording everything you eat and how you feel physically and mentally. Note any changes in energy, digestion, and skin clarity.

- Step 3: Controlled ReintroductionSlowly reintroduce soy in a specific form, such as a small amount of organic tofu. Observe your body’s reaction for 48 to 72 hours. If no symptoms appear, try a larger portion. If symptoms return, you have confirmed your sensitivity.

Nutritional Substitutes and Alternatives

Eliminating soy does not mean sacrificing nutrition or flavor. The modern market offers numerous alternatives that provide similar textures and nutritional profiles without the digestive backlash.

Dairy Alternatives

Switch soy milk for almond, oat, coconut, or hemp milk. For cooking, coconut milk offers a creamy consistency similar to soy creamers. Pea protein milks are also an excellent high-protein alternative for those who don’t have legume sensitivities.

Protein & Condiments

Replace soy sauce with Coconut Aminos—a sap-based sauce that is soy-free, gluten-free, and contains significantly less sodium. For tofu fans, “Hemp-fu” or chickpea-based tofu (often called Burmese Tofu) provides a similar culinary experience.

Replacing Key Nutrients

Soy is a complete protein, meaning it contains all nine essential amino acids. When removing it, ensure you are getting these from other sources. Quinoa, buckwheat, and the combination of rice and beans can provide complete protein profiles. Additionally, pay attention to Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D, especially if you were relying on fortified soy products for these nutrients.

Living and Dining Out with Sensitivity

Socializing and dining out are often the biggest hurdles for those with soy intolerance. However, with the right communication strategies, it is entirely manageable. Most modern kitchens are accustomed to dealing with allergies and intolerances.

- ✓Communicate Clearly: Don’t just ask if a dish has soy. Ask the server to check with the chef about the oil used in the fryer and whether any seasonings contain soy protein or lecithin.

- ✓Choose Cuisines Wisely: Some cuisines are easier to navigate. While East Asian food is soy-heavy, many Mediterranean or Latin American dishes rely on olive oil and corn-based products instead of soy.

- ✓The Fryer Risk: Be aware that most restaurants use vegetable oil blends (often primarily soybean oil) for deep frying. Even if the food itself is soy-free, cross-contamination in the fryer is common.

Managing the psychological aspect is also vital. It can feel isolating to have dietary restrictions, but focusing on the abundance of foods you *can* eat—fresh meats, fish, vegetables, grains, and fruits—rather than the restriction itself, can shift your perspective toward a positive, health-oriented lifestyle.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I still eat soy lecithin if I am soy intolerant?

Many people with soy intolerance can tolerate soy lecithin because it is a phospholipid, not a protein. Since the protein is what usually triggers the reaction, lecithin is often safe, though highly sensitive individuals should still exercise caution.

How long does it take for soy to leave the system?

While the physical soy particles may pass through your digestive tract in 24-48 hours, the inflammatory response and lingering symptoms like brain fog or skin issues can take 5-7 days to fully resolve after total elimination.

Is soybean oil safe?

Refined soybean oil usually contains very little soy protein, but it is not always protein-free. For those with a severe intolerance, it is best to avoid it in favor of olive, avocado, or coconut oils.

Is soy intolerance genetic?

While there isn’t a single “soy gene,” your gut microbiome’s composition and your family’s history of atopic conditions (like asthma or eczema) can increase the likelihood of developing food sensitivities.