The Evolution of FDA Health Claims: Navigating the Soy Heart Health Revocation

An in-depth analysis of the regulatory history, scientific shifts, and the landmark fda soy heart health claim revocation that redefined food labeling standards.

1. The Genesis of FDA Oversight

The journey of health claims on food labels began long before the sophisticated digital labels we see today. In the early 20th century, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) operated under a rigid mandate: any food product claiming to treat or prevent a disease was, by legal definition, a drug. This binary distinction left little room for the emerging science of nutrition and preventative health. For decades, manufacturers were largely prohibited from making health-related statements on packaging, leading to a void of information that consumers desperately needed to make informed dietary choices.

As nutritional science matured in the 1960s and 70s, researchers began to establish clear links between dietary patterns and chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The tension between the FDA’s strict regulatory stance and the growing body of evidence reached a breaking point in the 1980s. High-profile cases, such as cereal manufacturers claiming that fiber could reduce the risk of certain cancers, forced the agency to reconsider its position. The result was a radical transformation in how health information is communicated to the public, setting the stage for the rigorous, science-based framework we navigate today.

2. The NLEA Paradigm Shift

The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) of 1990 was the catalyst for the modern era of health claims. This legislation mandated standardized nutrition facts panels and provided the FDA with the authority to allow specific, science-backed claims regarding the relationship between a nutrient and a disease or health-related condition. The NLEA established the “Significant Scientific Agreement” (SSA) standard—a high bar that requires a consensus among qualified experts that the claim is supported by the totality of publicly available scientific evidence.

Under the NLEA, the FDA began authorizing specific claims, such as the link between calcium and osteoporosis, and sodium and hypertension. This era brought order to the “Wild West” of marketing, ensuring that consumers could trust the veracity of health claims. However, the rigidity of the SSA standard eventually led to legal challenges, as manufacturers argued that even emerging science should be shareable with consumers, provided it was properly qualified to avoid deception.

4. Case Study: The Soy Heart Health Claim

In 1999, the FDA authorized a landmark health claim for soy protein. Based on a meta-analysis of clinical trials, the agency concluded that 25 grams of soy protein per day, as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, could significantly reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by lowering LDL cholesterol levels. This was a monumental win for the soy industry and health-conscious consumers alike, leading to a surge in soy-based products on supermarket shelves, from soy milk to meat alternatives.

For nearly two decades, the soy protein claim stood as a prime example of an authorized SSA claim. It shaped dietary guidelines and consumer perceptions of plant-based proteins. However, the very nature of the SSA standard requires that claims remain consistent with the totality of evidence as it evolves. By the mid-2010s, new clinical trials and larger meta-analyses began to produce mixed results, casting doubt on whether the cholesterol-lowering effect of soy protein was as robust as initially believed. This divergence in data set the stage for a historic regulatory reversal.

5. The fda soy heart health claim revocation

In October 2017, the FDA took the unprecedented step of proposing a revocation of the authorized soy protein heart health claim. The fda soy heart health claim revocation proposal was the first time the agency had ever sought to withdraw an authorized claim based on the SSA standard. This move was not a dismissal of soy’s health benefits, but rather a recognition that the evidence had become too inconsistent to meet the high threshold required for an unqualified, authorized claim.

The agency’s review of the evidence revealed that while some studies still showed a benefit, many others found no statistically significant effect on heart disease risk. Under the fda soy heart health claim revocation framework, the agency proposed that the claim be moved from “Authorized” status to “Qualified” status. This means that while manufacturers could still mention the heart health benefits of soy, they would be required to use specific language acknowledging that the evidence is not conclusive. This transition highlights the FDA’s commitment to scientific integrity, even when it involves reversing a long-standing and widely accepted regulatory position.

The fda soy heart health claim revocation process has been a lengthy administrative journey, involving public comment periods and extensive scientific re-evaluations. It serves as a reminder that regulatory “truth” is not static; it is a reflection of the current scientific consensus. For stakeholders in the food industry, this revocation underscores the importance of continuous monitoring of nutritional research and the potential for shifts in labeling requirements that can impact branding and consumer trust.

6. Significant Scientific Agreement (SSA)

The concept of Significant Scientific Agreement is the bedrock of the FDA’s health claim system. It is not merely a majority vote among scientists; it is a qualitative assessment of the strength, consistency, and biological plausibility of the evidence. When evaluating a claim, the FDA looks for high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in humans that are representative of the general population. They also consider the potential for bias and the quality of the study designs.

In the context of the fda soy heart health claim revocation, the SSA standard was the tool used to determine that the data no longer spoke with a unified voice. The challenge for the FDA is balancing the need for consumer protection with the desire to promote beneficial dietary changes. If the bar for SSA is too high, valuable information is suppressed; if it is too low, the public loses faith in the agency’s endorsements. The soy case proves that the FDA is willing to adjust its sails when the scientific winds change, ensuring that authorized claims remain beyond reproach.

7. Implications for the Food Industry

The industry response to the fda soy heart health claim revocation has been complex. For many years, soy was the darling of the health food industry, and the heart health claim was a centerpiece of marketing strategies. The shift to a qualified claim requires companies to redesign packaging and reconsider their marketing narratives. This is not just a matter of changing a few words; it involves managing consumer perception. A “qualified” claim may be perceived by some consumers as a sign that the product is less healthy, even if the nutritional profile remains unchanged.

Moreover, this revocation sets a precedent for other authorized claims. It signals to the industry that no claim is “safe” forever. As technologies like nutrigenomics and precision nutrition advance, the data we have on common nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, fiber, and antioxidants will continue to grow. Manufacturers must now view health claims as dynamic assets that require ongoing scientific support. The cost of compliance, from legal reviews to label reprinting, can be significant, especially for smaller companies that rely heavily on a single health-focused product line.

8. The Future of Nutrient Profiling

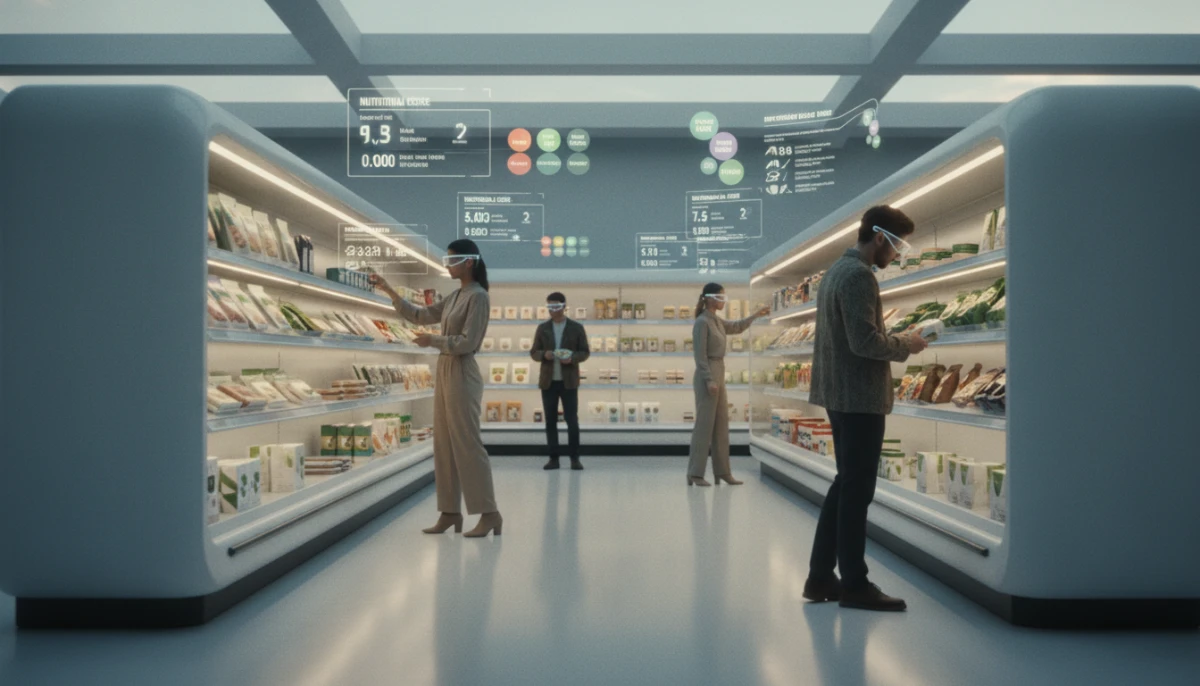

Looking ahead, the FDA is moving toward a more holistic view of nutrition. The agency has recently proposed a new definition for the “healthy” nutrient content claim, which focuses on nutrient-dense food groups and limits on added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats. This shift reflects a move away from focusing on single isolated nutrients—like soy protein—and toward a more comprehensive understanding of dietary patterns. The future of health claims may also incorporate digital elements, such as QR codes that link to the latest scientific summaries or personalized nutritional advice.

As we navigate the fallout of the fda soy heart health claim revocation, it is clear that the relationship between science, regulation, and the consumer is becoming increasingly sophisticated. The FDA’s role as a gatekeeper of health information remains vital, ensuring that in an era of misinformation, the claims on our food labels are grounded in rigorous, evolving science. For consumers, the message is simple: health is not found in a single claim or a single ingredient, but in the totality of a balanced, evidence-based diet.

Frequently Asked Questions

It means that the FDA no longer believes there is a ‘significant scientific agreement’ that soy protein alone reduces heart disease risk. Consumers may see modified language on soy products, moving from a definitive health claim to a qualified one that acknowledges the evidence is not conclusive.

Yes. The revocation is about the specific heart health claim, not the overall nutritional value of soy. Soy remains an excellent source of plant-based protein, fiber, and essential minerals, and can be a healthy part of any diet.

The process is extensive, involving public comment periods, scientific review, and legal assessments. The fda soy heart health claim revocation was proposed in 2017 and has undergone years of evaluation to ensure all viewpoints and data are considered.