Strategic Reconstruction, in the context of the Soy Online Service article (lavender.htm), refers to the alleged systematic rebranding of the soybean industry. It describes the historical shift where soy, originally viewed largely as an industrial byproduct for oil, paint, and plastics, was aggressively marketed and chemically processed to become a staple “health food” in the Western diet through calculated public relations campaigns.

Understanding Strategic Reconstruction in the Soy Industry

The phrase “Strategic Reconstruction” serves as a critical lens through which the history of the modern soy industry is viewed. Within the niche of nutritional investigation—specifically the content hosted on soyonlineservice.co.nz—this term implies a deliberate, orchestrated effort to alter public perception. The article referenced by the URL articles/lavender.htm is a seminal piece of literature for those questioning the mainstream narrative regarding soy consumption.

To understand this concept, one must look beyond the shelves of modern health food stores. The core thesis presented in such critiques is that the ubiquity of soy in the global food supply is not merely the result of organic demand or superior nutritional profile, but rather the outcome of industrial necessity. When production of soy oil skyrocketed for industrial uses, manufacturers were left with a massive surplus of soy protein mass. The “Strategic Reconstruction” was the industry’s solution: finding a way to monetize this waste product by rebranding it as a superior protein source for humans.

This perspective challenges the “health halo” that currently surrounds soy products. It suggests that the industry utilized lobbying, funded scientific studies, and marketing campaigns to obscure the traditional preparation methods of soy (fermentation) and replace them with modern, industrial processing techniques that may fail to neutralize naturally occurring antinutrients.

The Historical Context: From Industrial Byproduct to Superfood

The history of the soybean in the West is vastly different from its history in the East. In ancient Asian cultures, the soybean was primarily used as a cover crop or manure to fix nitrogen in the soil. It was not considered a major food source until the discovery of fermentation techniques, which created foods like miso, natto, and tempeh. These traditional methods were crucial for breaking down the bean’s potent enzyme inhibitors and phytic acid.

In contrast, the Western adoption of soy—the subject of the “Strategic Reconstruction”—began during the Great Depression and World War II. During this era, soy was championed by figures like Henry Ford, not necessarily for eating, but for manufacturing plastics, paint, and oil. The oil was the primary commodity; the protein-rich meal left behind was a byproduct, initially used as fertilizer or animal feed.

The turning point, as detailed in critical analyses like the Lavender article, occurred when the industry realized the economic potential of feeding this protein to humans. However, there was a cultural barrier: soy was associated with poverty and animal feed. The reconstruction of this image required a massive shift in marketing strategy. By the mid-20th century, technology allowed for the isolation of soy protein, leading to the creation of texturized vegetable protein (TVP) and other fillers that could be added to processed foods.

Deconstructing the Marketing Narrative

The success of the soy industry’s strategic reconstruction lies in its ability to pivot the narrative from “cheap filler” to “heart-healthy superfood.” This was achieved through decades of lobbying and the funding of nutritional research.

One of the most significant milestones in this reconstruction was the FDA’s approval of a health claim stating that soy protein may reduce the risk of heart disease. This claim allowed manufacturers to place “Heart Healthy” labels on everything from cereal to energy bars. Critics argue that this approval relied heavily on studies funded by the industry itself, while ignoring conflicting data regarding hormonal disruptions or thyroid function.

The narrative also leaned heavily on the “Asian Paradox”—the idea that because Asian populations consume soy and have lower rates of breast cancer and heart disease, soy must be the cause. However, the Strategic Reconstruction critique points out a critical flaw in this logic: Asian populations traditionally consume small amounts of fermented soy as a condiment, not large quantities of unfermented, highly processed soy protein isolate found in Western burgers and shakes.

Key Arguments Presented in the Lavender Article

The specific content associated with soyonlineservice.co.nz/articles/lavender.htm typically delves into the darker side of this history. While the exact text may vary across archives, the themes associated with the “Lavender” reference in this community usually focus on several core pillars of skepticism:

- The Validity of Safety Studies: The article likely questions the rigorousness of early safety testing, suggesting that short-term studies on rats were insufficient to predict long-term hormonal effects in humans.

- Economic Motivation: A detailed breakdown of how the profitability of the soybean crop drove the narrative, rather than public health interests.

- Suppression of Dissent: Accounts of scientists or researchers who raised concerns about soy isoflavones (phytoestrogens) and faced professional backlash or funding cuts.

This document serves as a manifesto for the “Soy Skeptic” movement, outlining how a legume containing potent anti-nutrients was reconstructed into a pillar of health through strategic maneuvering rather than nutritional merit.

The Controversy of Processing and Toxicity

Central to the argument of Strategic Reconstruction is the method of processing. The transition from traditional fermentation to industrial fractionation is where critics claim the danger lies.

Phytic Acid and Mineral Absorption: Soybeans have one of the highest phytate levels of any grain or legume. Phytic acid binds to minerals like zinc, calcium, magnesium, and iron, preventing their absorption in the gut. Traditional fermentation reduces phytate levels significantly. Modern processing, such as acid washing in aluminum tanks (a method often criticized in these circles), does not effectively remove phytates and may introduce other contaminants.

Enzyme Inhibitors: Raw soy contains trypsin inhibitors that can block protein digestion and cause pancreatic stress. While heat treatment reduces these, critics argue that the levels remaining in processed soy flour are still high enough to cause chronic digestive issues.

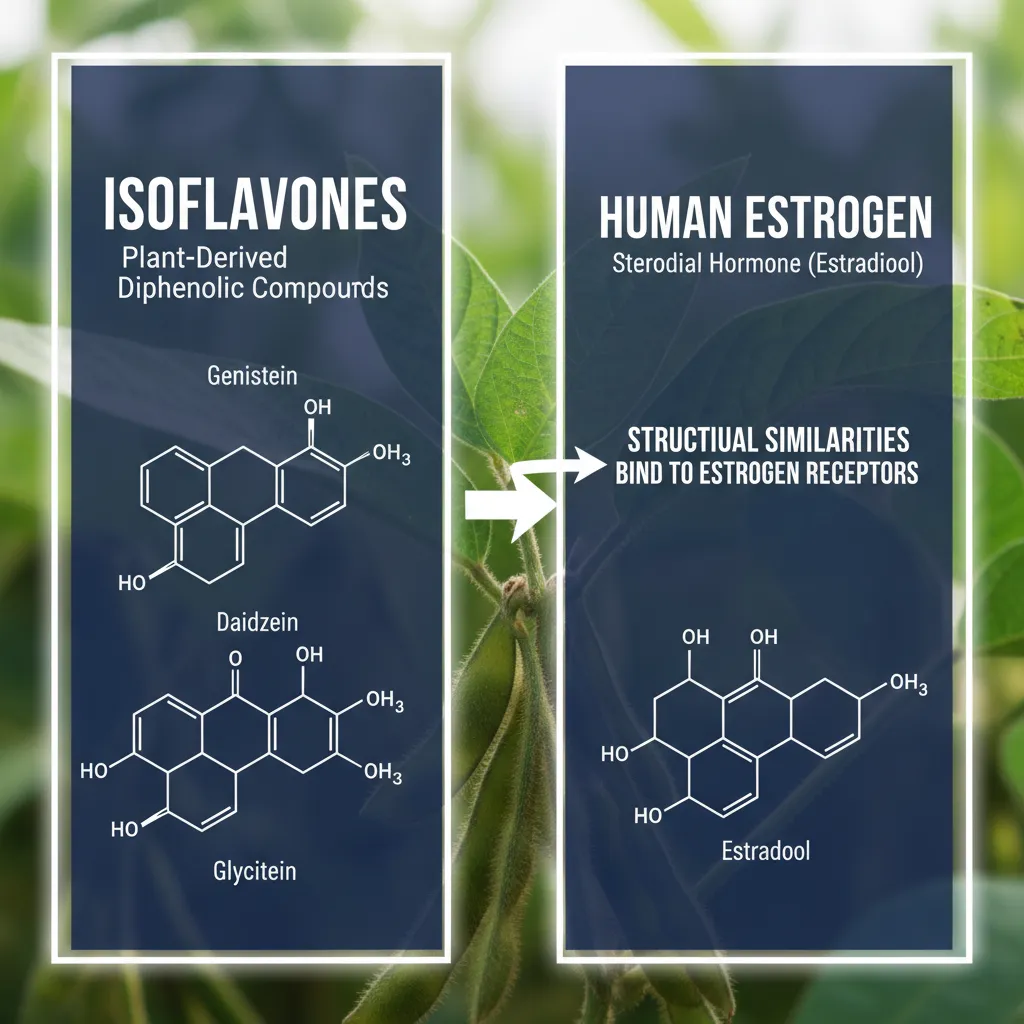

Phytoestrogens: Perhaps the most contentious issue is the presence of isoflavones (genistein and daidzein), which mimic the body’s estrogen. The “Strategic Reconstruction” narrative posits that the industry downplayed the potential endocrine-disrupting effects of these compounds, particularly for infants fed soy formula, labeling them instead as beneficial “antioxidants.”

Modern Implications and Consumer Awareness

Today, the legacy of this strategic reconstruction is visible in almost every aisle of the supermarket. Soy lecithin is a ubiquitous emulsifier; soybean oil is the primary cooking oil in the US; and soy protein isolate is the base for many plant-based meat alternatives.

However, the information age has allowed for a “counter-reconstruction” of sorts. Consumers are increasingly aware of the difference between fermented and unfermented soy. The rise of the Paleo and Keto diets, along with organizations like the Weston A. Price Foundation, has brought the arguments found in the Lavender article back into the spotlight.

Modern consumers are now asking more nuanced questions. It is no longer a binary debate of “Is soy good or bad?” but rather, “How was this soy processed?” and “Is this a traditional food or an industrial novelty?” This shift forces the industry to adapt once again, with many companies now highlighting “fermented” or “non-GMO” on their labels to distance themselves from the industrial image of the past.

Conclusion: Evaluating the Evidence

The “Strategic Reconstruction” of the soy industry is a fascinating case study in marketing, food science, and economics. Whether one views the soybean as a miracle crop that can feed the world or a toxic industrial byproduct masquerading as food depends largely on which historical narrative one accepts.

The document at soyonlineservice.co.nz/articles/lavender.htm represents a critical archive of dissent. It reminds us that our current perception of “healthy food” is often shaped by decades of corporate strategy as much as by nutritional science. For the health-conscious consumer, the takeaway is diligence: understanding the source, the processing, and the history of what we eat is the only way to make truly informed decisions.

For further reading on the regulatory history of food marketing and safety, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) archives provide the official timeline of health claim approvals that can be contrasted with the critical viewpoints discussed here.

People Also Ask

What is the main argument of the Soy Online Service?

The Soy Online Service primarily argues that unfermented soy products contain harmful antinutrients and toxins, and that the soy industry has used misleading marketing to promote these products as healthy despite potential risks to the thyroid and reproductive systems.

What does Strategic Reconstruction mean in the food industry?

In the food industry, Strategic Reconstruction refers to the deliberate rebranding and marketing efforts used to change public perception of a commodity—often transforming an industrial or waste product into a desirable consumer good through lobbying and advertising.

Why is unfermented soy considered controversial?

Unfermented soy is controversial because it retains high levels of phytic acid (which blocks mineral absorption) and trypsin inhibitors (which affect digestion), unlike fermented soy where these compounds are largely neutralized.

What are the alleged dangers of soy infant formula?

Critics argue that soy infant formula exposes babies to high levels of phytoestrogens (isoflavones) and manganese, potentially affecting hormonal development, thyroid function, and behavioral health, though health authorities generally deem it safe for term infants.

Who is the author of the Lavender article on soy?

The ‘Lavender’ article is often associated with the investigative work found on the Soy Online Service, likely referencing specific correspondence or a pseudonym used within the soy skeptic community to document the history of soy marketing.

How does fermentation change soybeans?

Fermentation breaks down the antinutrients found in raw soybeans, such as phytates and enzyme inhibitors, and increases the bioavailability of nutrients, making traditional foods like miso and tempeh easier to digest than processed soy protein.