Soy has long been a staple in Asian diets and, more recently, a subject of intense debate in Western nutrition circles. However, the conversation often misses a critical distinction: the difference between unfermented soy and fermented soy. While raw or simply cooked soybeans contain compounds that can inhibit digestion, the ancient art of fermentation transforms the humble soybean into a nutritional powerhouse.

For health-conscious individuals, particularly within the advanced food markets of New Zealand and Australia, understanding fermented soy health benefits is key to optimizing plant-based nutrition. Fermentation is not merely a method of preservation; it is a biochemical process that pre-digests complex proteins, neutralizes anti-nutrients, and creates entirely new bioactive compounds.

This comprehensive guide explores the deep science behind fermented soy, explaining why leading nutritionists and researchers advocate for its inclusion in a balanced diet over its unfermented counterparts.

The Science Behind Fermentation: Transformation at a Molecular Level

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In the context of soy, this usually involves specific bacteria (such as Bacillus subtilis for natto) or fungi (such as Rhizopus oligosporus for tempeh or Aspergillus oryzae for miso).

During this incubation period, these microorganisms feed on the carbohydrates and proteins found in the soybean. This biological activity results in enzymatic hydrolysis, breaking down complex macromolecules into simpler, more biologically active components.

The fermentation process acts as an external digestive system, breaking down long-chain proteins into absorbable peptides and amino acids before the food even enters your mouth.

This transformation is critical because soybeans are naturally dense with defensive compounds designed to protect the seed. Fermentation deactivates these compounds, unlocking the nutritional potential stored within.

Enhanced Nutrient Absorption and Isoflavone Bioavailability

One of the most significant fermented soy health benefits is the dramatic increase in the bioavailability of isoflavones. Isoflavones are a class of phytoestrogens that have been linked to reduced risks of hormone-dependent cancers, improved bone health, and menopausal relief.

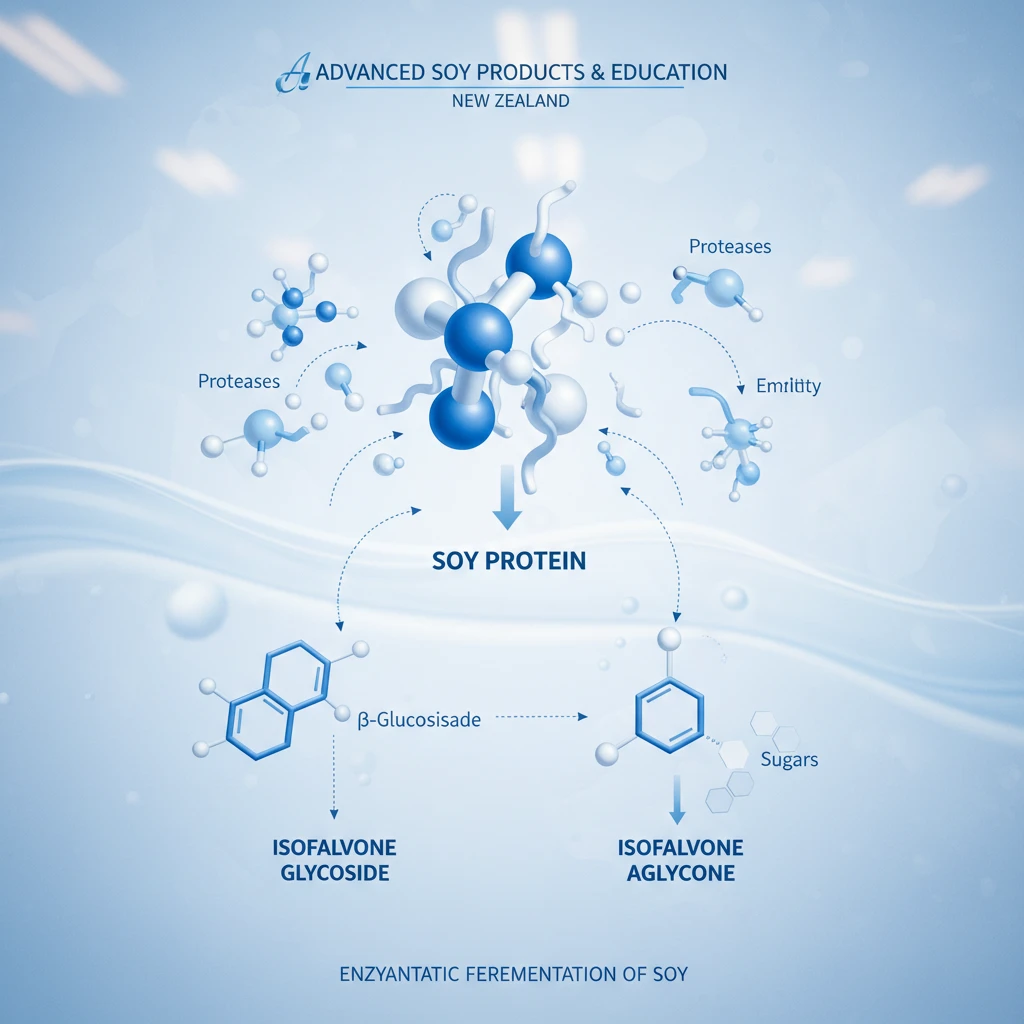

From Glycosides to Aglycones

In unfermented soy (like soy milk or tofu), isoflavones exist primarily as glycosides (bound to a sugar molecule). These molecules are large and difficult for the human small intestine to absorb. They must be broken down in the colon, a process that varies greatly depending on an individual’s gut flora.

Fermentation cleaves the sugar molecule from the isoflavone, converting it into an aglycone. Aglycones (such as genistein and daidzein) are:

- Smaller in molecular size.

- Absorbed directly in the small intestine.

- Significantly more potent in their biological activity.

Research indicates that the absorption of isoflavones from fermented soy products like miso and tempeh is significantly faster and more efficient than from unfermented sources.

Synthesis of Vitamin K2 (Menaquinone-7)

Perhaps the most unique benefit of fermented soy—specifically Natto—is the production of Vitamin K2, particularly the long-chain menaquinone-7 (MK-7). Unlike Vitamin K1, which is found in leafy greens and aids blood clotting, K2 is essential for directing calcium into bones and teeth and keeping it out of soft tissues like arteries.

Unfermented soy contains virtually no Vitamin K2. The bacteria Bacillus subtilis used in natto fermentation is a powerhouse for synthesizing this critical vitamin, making fermented soy one of the few vegan sources of K2.

Probiotics and the Gut Microbiome Connection

The human gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem that influences everything from digestion to mental health. Fermented soy products act as both probiotics and prebiotics, fostering a diverse and healthy microbiome.

The Probiotic Advantage

Products like unpasteurized miso and natto contain live active cultures. When consumed, these beneficial bacteria can transiently colonize the gut, crowding out pathogenic bacteria and producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which nourish the colon lining.

Prebiotic Fiber

Even if the soy product is cooked (like tempeh), the fermentation process modifies the soy fiber, making it an excellent prebiotic fuel for the resident good bacteria in your gut. This supports the integrity of the gut barrier and modulates the immune system.

Digestibility Advantages: Fermented vs. Unfermented Soy

A primary criticism of soy consumption revolves around “anti-nutrients.” These are natural compounds that can interfere with nutrient absorption. Fermentation is the most effective method for reducing these compounds.

Reduction of Phytic Acid

Phytic acid (phytate) binds to minerals like zinc, iron, and calcium, preventing their absorption. Fermentation produces the enzyme phytase, which breaks down phytic acid. This releases the bound minerals, making the iron and zinc in fermented soy highly bioavailable compared to raw soybeans.

Neutralizing Trypsin Inhibitors

Trypsin is an enzyme needed to digest protein. Raw soybeans contain potent trypsin inhibitors that can cause digestive distress and reduce protein absorption. While cooking reduces these levels, fermentation reduces them further, ensuring that the high protein content of soy is actually utilized by the body.

Comparison: Fermented vs. Unfermented Soy

| Feature | Unfermented Soy (Tofu, Soy Milk) | Fermented Soy (Tempeh, Natto, Miso) |

|---|---|---|

| Isoflavone Form | Glycosides (Low Bioavailability) | Aglycones (High Bioavailability) |

| Phytic Acid | Moderate to High | Significantly Reduced |

| Digestibility | Moderate (can cause bloating) | High (pre-digested enzymes) |

| Vitamin K2 | Negligible | High (specifically in Natto) |

| Probiotics | None | Rich source (if unpasteurized) |

| Flavor Profile | Neutral, Beany | Complex, Umami, Savory |

Pros and Cons of Fermented Soy

Pros:

- Superior Protein Absorption: Proteins are broken down into amino acids.

- Gut Health Support: Provides beneficial bacteria and reduces digestive strain.

- Mineral Density: Reduced phytates mean better iron and calcium uptake.

- Cardiovascular Support: Enzymes like Nattokinase support blood flow.

Cons:

- Acquired Taste: The strong smell and texture (especially Natto) can be challenging for some.

- Sodium Content: Products like Miso and Soy Sauce can be high in salt (though low-sodium options exist).

- Histamines: Fermented foods are naturally higher in histamines, which may affect sensitive individuals.

Traditional Uses and Modern Research Findings

Historically, Asian cultures have consumed soy primarily in fermented forms for thousands of years. Modern science is now validating this ancestral wisdom.

Tempeh: The Protein King

Originating in Indonesia, Tempeh is a cake of whole soybeans fermented with Rhizopus mold. Unlike tofu, it retains the whole bean, resulting in higher protein and fiber content. Modern research highlights Tempeh’s ability to lower oxidative stress due to its enhanced antioxidant profile post-fermentation.

Miso: The Daily Tonic

Japanese studies have long associated daily Miso soup consumption with reduced risks of gastric cancer and cardiovascular disease. Despite its salt content, research suggests that the unique peptides in Miso may prevent the blood pressure spikes typically associated with sodium.

The New Zealand Context

In New Zealand, there is a growing market for artisanal fermented soy products. Kiwi consumers, known for their focus on clean-label and functional foods, are increasingly adopting Tempeh and Miso not just as meat alternatives, but as gut-health supplements. Local producers are now experimenting with non-GMO, locally grown beans to create high-quality fermented options.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health Implications

The fermented soy health benefits extend deeply into metabolic health.

Nattokinase and Heart Health

Nattokinase is a fibrinolytic enzyme discovered in Natto. It has the potent ability to break down fibrin, a protein involved in blood clot formation. Clinical trials suggest that regular consumption of Nattokinase can help reduce blood pressure, improve blood flow, and lower the risk of deep vein thrombosis and atherosclerosis.

Cholesterol Management

Fermented soy protein has been shown to influence lipid metabolism positively. The peptides released during fermentation can inhibit the enzymes responsible for cholesterol synthesis in the liver, leading to lower LDL (bad) cholesterol levels without affecting HDL (good) cholesterol.

How to Incorporate Fermented Soy into Your Diet

Transitioning to fermented soy can be a culinary adventure. Here are practical ways to include these superfoods in your daily routine:

- Start with Miso: Replace bouillon cubes with organic Miso paste. Remember to add it at the end of cooking; boiling Miso kills the probiotic bacteria.

- Tempeh Bacon: Slice Tempeh thinly, marinate in smoked paprika and soy sauce, and pan-fry for a nutritious, high-protein sandwich filler.

- Natto Breakfast: For the brave, try Natto over rice with green onions and mustard—a traditional Japanese breakfast packed with Vitamin K2.

- Use Tamari: Switch from regular soy sauce to Tamari (a byproduct of Miso production), which is often gluten-free and richer in flavor.

By prioritizing fermented options, you ensure that you are not just eating soy, but absorbing the full spectrum of nutrients it has to offer.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is fermented soy safe for people with thyroid issues?

While soy contains goitrogens, fermentation significantly reduces these compounds. However, individuals with hypothyroidism should consult their doctor and ensure they have adequate iodine intake. Generally, fermented soy is considered safer for thyroid function than raw or unfermented soy.

Does fermented soy contain estrogen?

Soy contains phytoestrogens (isoflavones), which are plant compounds that mimic estrogen but are much weaker. Fermentation makes these more bioavailable, but current research indicates they do not negatively impact testosterone levels in men or increase breast cancer risk; in fact, they may offer protective benefits.

Can I eat fermented soy if I am gluten intolerant?

Many fermented soy products are naturally gluten-free. Tamari is a great gluten-free alternative to soy sauce. However, some commercially prepared Tempeh or Miso may contain grains like barley, so always check the label for “Gluten-Free” certification.

What is the best time of day to eat Natto?

Many experts suggest eating Natto at dinner. The enzyme Nattokinase is believed to be most effective at dissolving blood clots during sleep, and the Vitamin K2 aids in bone repair processes that occur overnight.

Is there a difference between fermented soy and hydrolyzed soy protein?

Yes, a massive difference. Fermented soy is a natural biological process using live cultures. Hydrolyzed soy protein is often processed using acid baths at high temperatures to create flavor enhancers (like MSG substitutes) and lacks the probiotic and nutritional benefits of traditional fermentation.